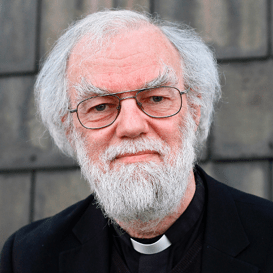

In this podcast, Rev. Rowan Williams reflects on questions that deeply touch our modern lives, drawing on the wisdom of the 4th century desert fathers and mothers. He encourages us to enter into the challenges and simplicity of the desert and find healing for our fragmented condition. You can read the full transcripts or listen to the podcast at the centre of the page.

Life, death and neighbours.

I want to express the warmest of thanks to the World Community for Christian Meditation for their invitation to be here. Because an invitation to address a group like this is always an open door into discovery for oneself. In preparing what I have to share with you in these few days, that’s been very much my experience a return to texts that are not entirely unfamiliar to me, but which, because I’ve had to think them through and pray them through with you in mind, have spoken afresh. So thank you for what you’ve already told me even before I tell you anything.

Why the Desert Fathers?

The inspiration of the World Community itself, the spiritual roots of John Main are so deeply interwoven with the desert tradition of early Christianity above all with the writings of the great Cassian that it seemed appropriate to look at those sources in a slightly wider context than simply thinking about meditation as such. To see where they might lead. It’s very clear in the writings of the great monastics of the 4th and 5th centuries that contemplation, meditation isn’t and can never be something in itself.

It is the fruit and the source of a renewed style of living together. It’s inseparable from the reality of the body of Christ. And what I want to do in these sessions is to look at certain aspects of how the life as a whole was understood by those early monastic writers. To see if we can be taken a bit further into understanding where the meditation came from and where it goes to.

Life. Death. Neighbours.

Because as we think about that, it seems to me, we touch on some of those wellsprings of renewal for our community as Christians. And so to this evening: life, death and neighbours. I’ve chosen those three words: life, death and neighbours for this first session because their words that are repeatedly interwoven in some of the recorded sayings of the first couple of generations of desert monks. You know, the essentials of the history that in the 4th Christian century, an increasing number of Christians worried by what they saw as the corruption or secularizing of the church of their day. Began to move into communities in the desert, some large, some small, many of them moved beyond that into solitude. Doing so in order to rediscover what it was that the church was there for. A question whose answer wasn’t always completely obvious in the fourth century as indeed it isn’t always completely obvious now.

Hence life, death and neighbours. Because our human life pivots around that cluster of realities for the desert monks. Some examples: you’re going to hear quite a lot of quotations in the next few days. In other words, I’m going to let other people do the work for me.

I'm quoting from the sayings of the Desert Fathers, translated by Benedicta Ward, a book which some of you, I'm sure will know and which I think is still in print and remains the best collection in English of the sayings of the Desert Fathers. From St Anthony the Great, usually regarded as the founder of monasticism, as we know it:

Further on and a generation or so later Moses the Black, an Ethiopian, an extraordinary, literally larger-than-life person. Abba Moses wrote: “The monk must die to his neighbor and never judge him at all in any way, whatever. A brother said: what does it mean to think in your heart that you’re a sinner? The old man said: if you’re occupied with your own faults, you have no time to see those of your neighbour. Our life and our death with our neighbour. If you gain the neighbour or the brother or sister, you gain God, you must die to your neighbour and never judge at all in any way, whatever.”

Gaining the neighbour or the brother or sister, in the language that St Anthony uses, seems very clearly to mean ‘winning them for God‘. In a sense, you might say converting them, Here’s a saying from Abba John the Dwarf:

They said: What does that mean? He said: “the foundation is our neighbour whom we must win. That is the place to begin. Every commandment of Christ depends on this one. To win, to gain the neighbour is to put them in touch with God. It’s that reality of putting someone else in touch with God.

That I want to suggest is fundamental for a great deal of understanding the spirituality of the desert. And the failure to put someone in touch with God, to create an obstacle in another’s path is a kind of rebellion against Christ.

Now, the desert fathers are very interested in what gets in the way here. In how we put obstacles between other people and God. They were well aware that one of the major temptations of being religious is to intrude between other people and God. We like to think that we know more about God than they do. We like to think that it’s comfortable for us to control the neighbour and their access to God.

And you can read a good deal of the history of the church as a sustained attempt to police one another’s relationships with God, on the part of Christian people.

The desert fathers didn’t escape that by going to the desert. On the contrary, in many ways, they were concerned to draw it out with greater and greater clarity. To encourage and foster greater and greater honesty about how we get in other people’s way before God. And there are a number of instances which they habitually refer to, of this kind of getting in the way.

A kind of inattention to somebody

One interestingly is a kind of inattention to somebody else. Inattention meaning we think we know what they need and that almost always arises from a failure to attend to what they really are. Not attending to what a particular person can hear, or what a particular person can bear at any one point. That’s something which occurs again and again.

There are several versions of the story in which a young monk comes to an old one in despair and says: “I have temptations, I have problems of this or that kind. And I went to father so and so who said: this is terrible! You must do 17 years penance, and I’m not sure that I can stand 17 years penance: Have you got any advice for me, father? And the old man almost invariably says: go and tell father so and so: Father so and so, who has recommended 17 years penance, has not been paying attention.

Part of that, of course, relates to the concern shown by so many of the desert fathers about inappropriate kinds of harshness. Looking down on others, arising from a kind of self-confidence, which is not appropriate.

I think here the most important development which has brought this about is the coming of 17th-century natural science based on the idea that there is no moral distinction to be made between different forces and different causes of laws and so on with which we explain the universe around us. So that’s the second kind of disenchantment, we live in that sense, a disenchanted world, a world of science and I try to put those two developments together and to say that we live what I want to call in an imminent frame today.

Macarius the Great

Macarius the Great and Piemem. Those two are remembered specifically for this. Of Macarius, we read unforgettably, that it was said that he became like a God in sketes, the monastic area. Because when he saw the sins of the brothers, he would cast the cloak of his mercy over them. That’s what God is like. That’s what Macarius is like.

Macarius is visiting another brother called Theotemptus. When he was alone with him, the old man asked: How are you doing? Theotemptus replied: thanks to your prayers. Fine.

The old man asked: Do not your fantasies war against you? He replied: No, up to now. It’s all right. He was afraid to admit anything. The old man, Macarius said to him: many years, I’ve lived in an aesthetic and everybody praises me. Though I’m an old man, I still have a lot of trouble with sexual fantasy.

Theotemptus said: Well, actually Father it’s the same with me. The old man went on admitting one after another, that other thoughts warred against him until he had brought Theotemptus to admit all of them himself.

Being harsh on harshness recurs in many ways.

Aber Pieman brother questioned the Pieman saying, I’ve committed a great sin. I feel I must do three years penance. The old man said: that’s quite a lot. The brother said: What about one year? The old man said, That’s still quite a lot. 40 days? Pieman said: That’s a lot. For myself, I think if somebody repents with all his heart and does not intend to commit the sin anymore, perhaps God will be satisfied with just three days.

Harshness often comes from and goes with claims of superiority. And we’ve already seen how Macarius in particular turns that on its head. The gift of the spiritual director, the father, the Abba here in gaining the neighbor is a gift which has to do with identification. You can’t say anything.

You can’t get anywhere unless first and foremost, the father, the director, the senior has put himself or herself on the level of the person asking the question. Hence Macarius is wonderful, therapeutic exposition of his own weakness. So that the self satisfied old monk gradually sees that it’s all right to admit his.

Another scapegoating story

And another story that recurs in a variety of forms is about occasions where the community at large has been eager to pass sentence. And one of the great old men has countermanded it. There was a brother at sketes who committed a fault. They called a meeting and invited Abba Moses. He refused to go – sensible man. The priest sent someone to say to him: Everybody’s waiting for you. So Moses got up and went, he took a leaking jug and filled it with water and carried it with him. The others came out to meet him and said: what is this father?

The old man said to them, my sins run out behind me and I can’t see them. And here I am coming to judge the errors of somebody else. When they heard that they canceled the meeting.

A matter of friction between superiority & harshness

The claims of superiority inherent in the eagerness to judge are again part of those obstacles we place between God and the neighbor. Repeatedly, as I say, we have a great old man like Moses and there are others refusing often in very dramatic ways to take part in a kind of group scapegoating story, again, as told of several people, they are invited to a council, as is Moses in that story and judgment is passed. The great old man, whoever it is, gets up and walks out: Where are you going, father? I have just been condemned.

All these hang together as part of one indissoluble vision of spiritual and relational therapy. Inattention to the reality of the other leads to harshness, harshness has to do with superiority.

And that’s why dying to the neighbor is part of living with the neighbor. The monk must die to his neighbor and not judge in anything. Like Macarius covering the sins of the brother as if he did not see them. And Abba John’s question ‘who am I?’ It’s not a kind of indifferentism that sin doesn’t matter. It’s just that the one place you can be certain of recognizing failure and alienation from God is in yourself. Hence the advice given by Moses to Pieman: If you have sin enough in your own life in your own house, there’s no need to go looking for it elsewhere. Or as another father puts it rather more graphically when you have a corpse laid out in your own front room, you don’t have time to go to a neighbor’s funeral.

The healing solidarity

That is a way not of minimizing the seriousness of failure, but recognizing that failure is only healed by humility and solidarity and not by condemnation.

How is sin to be dealt with? Temptation is always to say, I know how to deal with that in you. Not so sure about myself, but I know how to deal with it in you. The desert fathers are consistently saying: you deal with it first and foremost, remember Abba John the Dwarf. Don’t start from the roof. You deal with it first and foremost by standing with the sinner. Whatever is the matter, you are to be there alongside them. First, last and always. And again, a few examples: a brother questioned a man saying: if I see my brother committing a sin, should I conceal it? The old man said at the moment when we hide our brother’s fault, God hides our own.

At the moment when we reveal our brother’s fault, God reveals our own. Some old men came to see Abba Pieman and said to him we see some of the brothers falling asleep during the divine office. Should we wake them up? He said as far as I’m concerned, when I see a brother who is falling asleep during the divine office, I put his head on my knees and let him rest. No, not indifference, but where do we start with the identification? Solidarity. That is what heals.

Winning our neighbour for God?

If we’re trying to reimagine what it is to lead the Christian life together, I think I would underline particularly two words which need redefining. One is life. One is gain. Life here, the life that is with the neighbour is primarily and precisely the life that is being free to let God give through you, being free to let God give through you. Because all these various pathologies of the spirit which arise in the common life.

The urge to cement your superiority, the urge to pass judgment and to shut out all of these are ways of not allowing God to give through you. Gain, gaining the brother gaining. The neighbour, gain is conceived purely and simply as the freedom that comes from that transparency to God, as it’s experienced by another person. And that puts some very severe questions to a lot of what we take for granted about common life.

What if the real criteria for vital common life had to do with our failure or success in connecting another person with the possibility of reconciliation or of wholeness?

Whether we are able to connect someone else with reconciliation wholeness and we connect not by successfully ordering their lives towards reconciliation and wholeness. Not by triumphantly solving their problems, as we would love to do. We connect by our own willingness to face our weakness and our thoughts. Our own connectedness with God’s mercy. To live like that requires obviously a pervasive critical awareness of how much in church and world we are encouraged to be competitive. To imagine success in terms of the others loss when we pretend it isn’t so.

But as a matter of fact, in church or world, that’s the model we work with. I sometimes wonder what life in the church would be like if we had never developed the concept of winning and losing.

In many of the great controversies that face the church at the moment. Many of those controversies, it seems to me increasingly clear that nobody is going to win. In other words, there is not going to be situation of sublime clarity in which one group’s views will prevail, because the other group simply says, oh, I see it all now. But if we’re not in the business of winning and losing like that, what does the Church look like? What if we were sufficiently unafraid? There’s a keyword ‘sufficiently unafraid‘ to be able to put winning and losing on the back burner, to move away from the notion that my triumph is another’s loss.

What if we were able to think of the health of the Christian community in terms of our ability, or otherwise our freedom or otherwise, to connect one another with the wellsprings of reconciliation? We may not know positively how to do that in a triumphant and comprehensive way.

What do the desert fathers teach us?

The desert fathers do at least give us some fairly searching criteria which help us to know how not to do it. Dying to the neighbour is not being afraid. And that can only come, as I’ve said, from the sense of our own deep connectedness with the mercy of God. It’s easy to caricature this as a faintly complacent picture. Nobody’s going to win. So why struggle? Nobody knows who’s right? So why bother. God is always merciful, so why not relax? God will forgive, that’s what we pay him for. That’s one of those great 18th century French cynics observed. What makes this not complacent in the desert fathers especially, I think, is that a pervasive sense of shared frailty. Macarius, Moses, Pieman and all the other great names are at one at the same time, strenuous and relaxed. Most of us know what it is to be strenuous, know what it is to be relaxed, but we’re not very good at holding them together.

We think strenuousness is tension, being strong to a tight pitch. We think relaxation is a sort of slackness, a letting go. What I read in the sayings of the great old men and women of the desert is something that doesn’t easily fall into those rather cliché terms. There’s an extraordinarily poignant sense of sin. Sometimes a young monk will say to an old one: we so admire your penance and your aestheticism. Don’t you think you’ve earned your way to heaven by now? And the old man says: no, if I had three lifetimes, I couldn’t make up for the mess I’ve made of my life. Take that out of its context, and a sort of Lutheran objection arises. Don’t these people believe in the free grace of God? The answer, I think is, yes, they do, and that’s why the awareness that they have, of this frailty, of his sinfulness which even three lifetimes couldn’t atone for goes hand in hand with the extraordinary tenderness that they ascribed to God and show to one another.

If your sins are that serious, then you may very well spend a lifetime weeping and doing penance not because you’re making something up to God, but because that’s how it is to experience yourself as a failure. A sinner and a sufferer. But so far from that providing a whole catalog, a whole system of condemnatory regulation that is precisely what allows you to hear and to understand the tears and the self hatred of somebody else.

Let me go back to a phrase I used a bit earlier. Sin is healed by solidarity. The monks of the desert. We’re looking for solitude but not isolation. A good deal of research has been done in the last couple of decades on the importance of community to these people. The way in which time and again in the narratives and the sayings that stem from them, time and again, the point is reinforced only in the relations they have with one another.

Can the love and the mercy of God appear and become effective? And those mutual relations have to do with that identification, that solidarity, that willingness to stand with the accused and the condemned.

And somehow it’s in that action that the real healing occurs, prayers and fasting. sleepless nights and asceticism. Well, various of the fathers take varying views of it. Most of them are rather skeptical about how significant that is. But, if you are able in some sense, to take away what in you stands between God and the neighbour then your own healing, as well as the other person’s healing, is set forward.

So asceticism is not simply about loading your body with chains, spending 30 years on top of a pillar, sleeping two hours a night or whatever.

Asceticism is a purification of seeing. It’s not a self punishment, but a way of opening the eyes. The whole of this life is about becoming instrumental to someone else’s path to reconciliation.

It may well be that we arrive at heaven if we ever do slightly puzzled by how we got, there is no doubt we all shall be and it has explained to us that we’re there quite simply because at some moment or other we served another’s path to reconciliation. And maybe we barely noticed it. But that’s what we’re there for. For each one of us to find how exactly we are to be. The means for someone else to connect with reconciliation will be very different depending who we are, what our responsibilities are, what our own inner blockages are as well. And the way in which each one of us overcomes his or her instinct towards exclusion or judgment that will depend on a great deal to do with our histories and our temperament.

Nonetheless our life and our death remain with our neighbour. Our life is with our neighbour because we are alive in God, when and only when, God’s reconciling presence is through us, somehow connected with the reality of the neighbour. Our death is with our neighbour because letting go of all of these things which we so love, the moral high ground. The conviction of victory is a kind of death: if we gain the neighbor, we gain Christ because it’s as we connect the other with the source of reconciliation that we come to stand in the place once and for all, cleared for us and defined for us by Jesus Christ. Our life and our death our with our neighbor. If we gain the neighbour, we gain God.

Top image by Jörg Peter from Pixabay

St. Anthony’s picture by Image by JackieLou DL from Pixabay