The biography of Thomas Berry, author of The Dream of the Earth and The Great Work, gives a detailed account of a significant moment in his life. Flying back to the US from an environmental conference in the Seychelles at some point in the 1970s, it reports that he looked down on the River Nile from 30,000 feet and realised that he was no longer a theologian, not even an eco-theologian, but that he had become what he now had to be: a geologian. Pausing only to note the ironic arrival of this epiphany on board one of the chief carbon-emitting enemies of the good Earth, it’s worth pointing out that this is the same Thomas Berry who advised the faithful to “put the Bible on a shelf for 20 years.” He was not shy about breaking moulds, thinking outside the box or ruffling feathers. His work ushered in a new sense of urgency for those of all religions, or none, who were concerned about the fate of the planet. He directed our attention to the immediate dangers that were there right in front of us – if we had eyes to see – and also firmly towards the future: our role in the evolutionary history of the species, the planet, the Universe.

Building a Better World for All

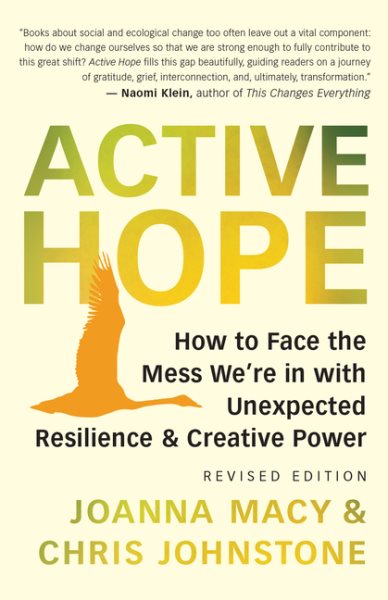

A geologian is close to what Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone are urging us to be in the revised edition (2022) of their important and necessary book ACTIVE HOPE: How to Face the Mess We’re in with Unexpected Resilience & Creative Power. Another term for what they encourage you and me to become is a bodhisattva. This is the name for any person who has committed to the path of awakening bodhicitta, the clear and compassionate mind which works for the benefit of all sentient beings – including, of course, the Earth herself.

Joanna Macy – 93 years old, a celebrated activist, a proponent of deep ecology and an influential teacher since the 1970s – is a Buddhist scholar and practitioner. In many ways her book is simply a manual of applied Buddhist ethics and practice. It’s a kind of Buddhism 101, only not in the form of a simplistic beginner’s manual. It just happens to be addressing the most urgent challenge that humanity has ever faced. And one that, ironically, demands of us that we return to beginner’s mind.

The book is indeed co-authored, and though it is clear that the less well-known and less celebrated Chris Johnstone has himself put in many creative and influential years as a sustainability activist, it is impossible not to feel the dynamic presence of Joanna Macy very much to the foreground throughout the pages of Active Hope. She is the superstar in this partnership – a title that her drive and charisma over many decades has justifiably earned her (and one that she would surely resist).

The underlying and unspoken conviction of the book is that if we were all bodhisattvas – or indeed good Christians, living joyously other-centred lives – then we would not be in the mess that we’re in, facing habitat devastation, mass extinctions, wars, social injustice and global suffering on an unimaginable scale. And what it is to be a ‘good Christian’ is every day becoming increasingly clear and obvious (again, if we have seeing eyes, listening ears, open hearts.) It’s safe to assume, for instance, that Thomas Berry’s shift to “geologian” spoke of a desire, shared by many, to move away from a religious sensibility that is overtly or unconsciously focused on a project of private and personal salvation. Too much of the Christian enterprise (some would be tempted to say too much of all religious activity and discourse) is about defending and sustaining the separate, individual, fragile self or its larger aggregates, cultural and national identity. All too often it has been simply another project of the fearful and imperial ego, convincingly disguised as ‘spirituality’.

This is the consciousness that takes us beyond the increasingly desperate survival strategies of the ego – that limited and defended version of self. It is the consciousness that knows at a deep, even a cellular level that ‘it’ is not separate from the ocean lapping at the body’s toes, from the blue tits at the feeder in the garden, from the wounded, gasping forests of the Amazon, from the soil that you will become, from the plants that will eventually eat you, from the stardust whence you came.

A shared identity with the natural world

That unitive vision is at the heart of all mystical seeing (where ‘mystical’ is best understood as simply ‘not separate’ – perhaps ‘contemplative’ is a less distracting and misleading term.) The sense – the experience – of an intimacy and a radically shared identity with the so-called ‘natural world’ (though even calling it that is strangely objectifying and alienating) is vividly present in the great tradition of eco-contemplatives: names such as Hildegard of Bingen, St Francis of Assisi, Emily Dickinson, Emerson, Thoreau, Teilhard de Chardin, Thomas Berry himself. If we really knew, like them, the truth of the Upanishad’s tat tvam asi – “you are that” – with its insistence on the non-separation between the individual being, the ineffable Absolute and everything that arises from that Absolute, then how could we ever do any harm to each other (to ourselves)?

The virtue and the genius of this book is that it honours the work of visionaries such as Berry by embracing it and taking it further. It does this by seeking to encourage and equip us as we take our next, and necessary, evolutionary steps. For this is an immensely practical book, bringing our concern for the planet helpfully down to Earth. It gets right alongside us, recognising and naming our usually hidden (or insistently repressed) guilt, terror, laziness and despair about what we are witnessing – and sometimes pretending not to see.

This very process of naming is itself one of the key transformative strategies in what Macy and Johnstone are urgently and compassionately offering their readers. In many ways their great gift is to provide us with a new vocabulary with which to see more clearly the Earth as it is and – crucially – the Earth as it could be. The very title of the book isn’t simply a descriptive conjoining of two useful qualities. The term “Active Hope” (significantly capitalised throughout the text) is a lot more than the sum of its two parts. Rather than being the marker of something generically aspirational, it offers a name for a radically different way of inhabiting reality. The book’s introduction spells out the kind of metanoia that we are being invited to undergo. Active Hope, it tells us, is something we do, rather than have. Like tai chi or gardening, it is a practice. Most helpful and liberating of all, it goes on to tell us that since “Active Hope doesn’t require our optimism, we can apply it even in the areas where we feel hopeless.”

What happens through you?

There are many namings, renamings and neologisms offered throughout the book, giving us the opportunity to experience ourselves, each other and our suffering Earth in ways completely different to those we have previously settled for – or had sold to us. Three of the most useful and (literally) world-changing of these coinages are The Great Unraveling – the clear recognition of the world’s collapsing systems; Business as Usual – the insistent belief and demand that economic growth is all that matters; The Great Turning – “the epochal transition from the industrial growth society to a life-sustaining society”. The naming of these stories – the stories that we choose to identify with and live from – widens and dramatizes the life of each one of us. To which of them shall we give all of our attention, our energy, our life? (Because we do have to choose.) As the authors put it, in a starkly personalising question, “What happens through you?”

The rest of the book is a detailed menu of thought experiments and action experiments that you can try out by yourself or – infinitely preferably – with others. One of the many refreshing things about Active Hope is that, unlike many other books, it points urgently beyond itself to the action that we must all take, the different lives we must lead. And, helpfully, it can point immediately and directly to a myriad ways in which the reader can get active and hopeful (even in the midst of acknowledged despair) via many linked resources: www.activehope.training or www.workthatreconnects.org

This is not necessarily the most entertaining, the best written, or the most congenial book that you will ever read, but it may very well turn out to be the most important one. In many ways – probably all ways – that is up to you. One of the most engaging and provocative chapters is called “A Larger View of Time”. It is filled with images, information and yet more thought experiments designed (successfully, I can report) to utterly transform your sense of past, present and future. At one point there is a description of the Native American Haudenosaunee people who, when they meet in council to consider major decisions, always ask, “How will this affect the seventh generation?”

Our great fear about the fate of the Earth and all the creatures on it is being increasingly acknowledged and voiced. But perhaps there is an even greater, more secret fear: that we actually do have the ability to choose, to ask the infinitely wise questions that the Haudenosaunee are prepared to ask. Active Hope brilliantly shows us that within and beyond that very fear lie our unexpected resilience and creative power. We can become the geologians that we really are.

2 thoughts on “Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We’re in with Unexpected Resilience & Creative Power.”

Thanks for your thought provoking review Jim….I read the original book and was inspired by how empowering it was so it will be definitely worth getting this updated version and sharing its wisdom.

I have been needing this book for some time .My daughter offered me “climate crisis counselling “ through a friend of hers .Thankyou Jim for your in depth review of Active Hope:How to face the Mess we are in .I think it will help me be positive in how to Live with this .