The Chavet Cave in Southern France, discovered about 20 years ago, contains the earliest known works of art – to say human works of art would be redundant, of course, as only the human is a maker of the artificial. Other animals make tools to serve a practical purpose in the struggle to survive. Humans alone are so intrigued and seduced by reality that they try to reproduce it in order to understand it better. The cave paintings, of lions, bison and rhinoceros, are almost entirely of the animal world; and the few human figures seem to merge with their animal totems as in ancient, much later myths.

We look at these powerful and loving representations of nature with an intimate resonance. We recognize and understand the both instinctive urge to represent and its way of relating to the world around us. But there are no words or other indications of the beliefs or rituals that related to the art. As with stone circles, and all prehistory, we feel simultaneously close and distant to our ancestors. Pre-history is silent.

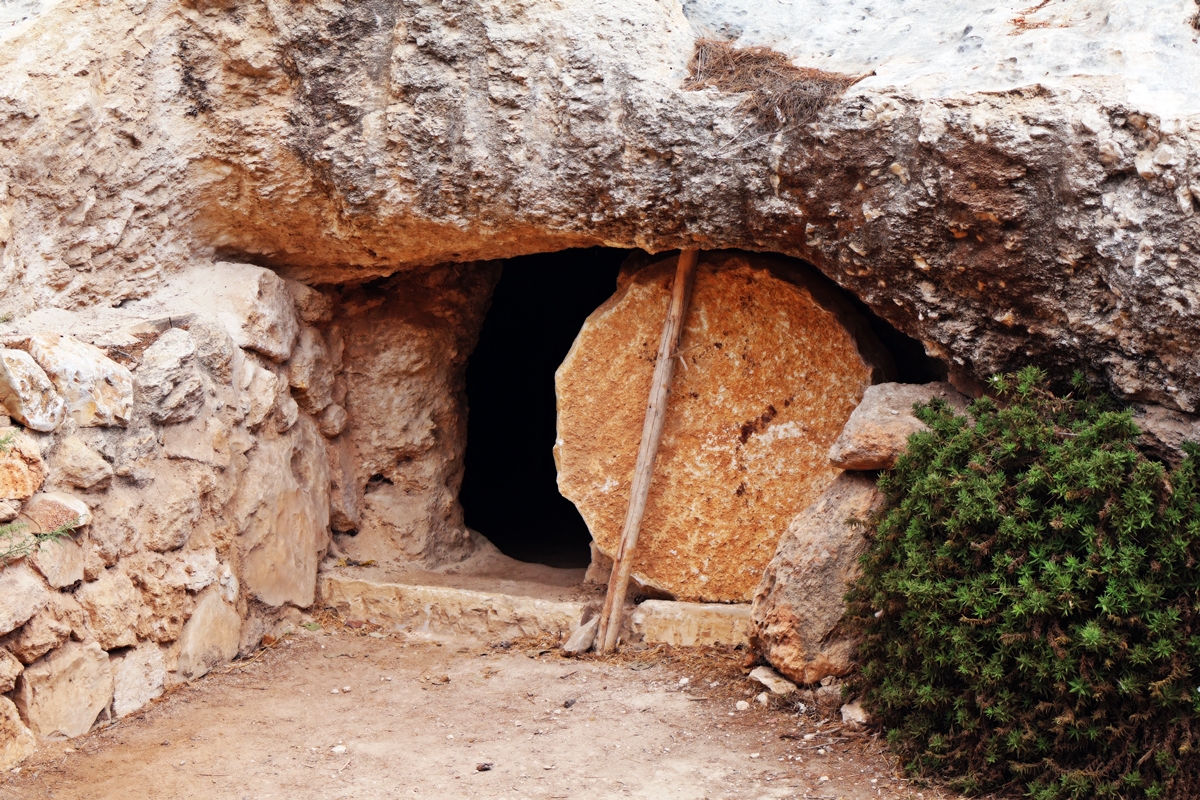

In later stories, such as those we have been preparing for the past few weeks to re-tell in Holy Week, culminating in the great tribal night fire at the Easter Vigil, we share a historical context. Words have come down to us and we try, even if imperfectly, to understand their meaning. History speaks.

But there is a third stage in the human quest that is the eternal present. We are mistaken when we project it into the future. The future is only another metaphor. The always present has a different kind of silence, post-verbal and post-imaginative. It is not about re-presentation, either verbal or visual, precisely because it is present. Everything in time points to this. And when we come to it we are home.

Laurence Freeman OSB

Listen to the Lent Daily Reflections Podcast HERE