In this episode, Laurence Freeman OSB introduces meditation in the very simple tradition in which is thought in the World Community. Whether we’re absolute beginners or we’ve been meditating for many years, every time we listen to essential teaching of meditation, we always understand it freshly and in a new way. Meditation is as old as humanity itself. It is a universal practice, arising in – and uniting – all wisdom traditions throughout the world. Listen to the full podcast here or read the full podcast notes from this podcast below.

Podcast notes

Teaching meditation to children thought me…

When teaching meditation to young children, I will often do that. In fact, now I always do it just begin to attract their attention, asking them to listen to the sound of the bell or the gong whatever they’re listening to, just to listen to it with attention.

And then I asked them to put up their hand when they can no longer here it. So they are really engaged with it as a kind of game, and I think there couldn’t be a better way of understanding meditation by them by speaking about it with children and meditating with children and the ideas and the concepts that could become very complicated and sophisticated when we speak about them in an adult way, for them are very immediate, very simple and very tangible, very sensory. And rather than thinking about meditation as a difficult skill, they’ve got to master or ascetical path, they have to follow. They see it as a way of playing and if we could think of wisdom as playing before the throne of God, which is how it’s described in the Bible, and we could think of ourselves as playing like children in the presence of the Spirit, I think we would be much closer to understanding why meditation is a supreme source of wisdom for us and for our time.

Introducing meditation

I think a good number of us here I’m told are new to meditation. So let me introduce meditation in the very simple tradition that we teach it within the World Community. And for those of you who would be meditating for several decades, you should know by now that we are always beginners and that every time we hear this essential teaching, if we listen to it, then we understand it freshly and in a new way. Let me begin with a quote that I’ll be using and during the talks and the retreat from the first letter to the Corinthians:

“The image of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing and lost. But to us, it is the power of God. Has God not made foolish the wisdom of this world? God chose the foolish to shame the wise and the weak to shame the powerful.”

If you really want to understand the meaning of those words, then learn to meditate and keep learning to meditate for a long as you are alive, because when you first meditate and on many other occasions you will feel very foolish about what you’re doing. The wisdom of the world, which is that you should be doing this successfully, you should be mastering it, is shamed by the foolishness of God, by the experience of wisdom that we’re led into.

Meditation is as old as humanity. One student in a primary school class once asked me, a rather precocious child maybe, after the meditation: “Who invented meditation?” Maybe he was thinking of Harvard in 1960 but I had to think fast on my feet. I said: “Well, I think God invented it. God invented it because he wanted us to find him. And meditation teaches us that God is always within us.” So I looked at him hoping I’d get a good rating, and he seemed satisfied with that.

The etymology of meditation

We find meditation in all of the great religious traditions. The wisdom of a word of any word in any language is often found in the roots. The etymology in the roots of that word and in the many different ways it’s used. And the word meditation has this prefix med: a very common prefix in Indo European languages. It suggests taking appropriate measures, is one way of describing it or giving care and attention. And so, not surprisingly, it gives us the word medicine. When you go to see a doctor or nurse, the one thing you would really like to receive from them is care and attention, and that they take the appropriate measures.

But it’s a very rich word. In fact, it carries with it the sense of being aware of what is there and of also being aware of what is only seeming to be there. Seeing the difference between appearance and reality, between truth and illusion. We see, first of all, the connection with health and so with the whole mystery in the human condition of healing. Who of us is not concerned with healing? And also with the realisation of wholeness, the ultimate wholeness that we always see beyond ourselves and yet somehow touching us. This word meditation is also present, the root of the word, in other words, we use all the time words like moderate or moderation to modify just to change things so that it’s right to modulate to attune something correctly. So it suggests also right judgment, being able to do the right time at the right time or being mindful, being aware, being awake.

And it even gives us the word modern, which means being in the moment, being up to date. So all of this is just enough, maybe to suggest that meditation is a way to wisdom. Wisdom is illustrated by all of these things I mentioned: care, attention, discrimination, truth. Wisdom, like meditation, is seen in all human traditions as something natural, something we are born to discover, born to know, born to practice. Something universal and essentially, as children know, simple. Often I found over the years that people are meditating without knowing it. Or they’re coming very close to what we would understand as meditation without fully knowing it yet, and then it just needs a small tap or a gentle push on and they awaken to it and they jump in. And they discover that this is a discipline and they embrace the discipline because they understand that discipline means learning. It’s a way, a path of learning.

John Main and meditation

John Main has channelled to us or communicated to us through his teaching our own Christian tradition of meditation. But that tradition of meditation and Christianity became very marginalized, became a source, often object of suspicion or of even of persecution, as it has in other religious traditions. So when John Main was a young diplomat in the Far East before he became a monk and he met an Indian monk who impressed him very deeply by his wisdom and by his compassion. As they began to talk about the spiritual life on this led the monk to speak about meditation, John Main began to listen very carefully as a Christian, as a person who took his faith and his spiritual journey very seriously. And the Swami introduced him to a way of meditation which both seemed new but also familiar to him.

And it was too see meditation as a radically simple way of prayer: A journey from the mind to the heart, from thought to silence, from images to pure vision. And as he listened, it created resonance and echoes for him in his own knowledge of his own Christian tradition But when he heard the teaching on how to do this, that his teacher gave him, it triggered other associations of repetitive prayer because the monks said to him: What he could do would be to take a single word or a short phrase and repeat this word or phrase continuously in the mind and heart during the time of the meditation. Listening to the word as you say it and leaving aside, letting go off all thoughts, words and imagination. He asked the monk: Could you teach me as a Christian to meditate? The monks said well, of course: It will make you a better Christian, he said. And if you are serious about it, you can come and meditate with me once a week and I’ll try to help you. But the most important thing is that you do it yourself. And that’s what he meant by being serious, that he did it and he suggested that he do it every morning and every evening, which he did.

Later in his life, John Main became a monk, a Benedictine monk, when he spoke about this way of prayer that he had learned and had integrated into his Christian spiritual life, his novice master, in the 1950s, said: “Well, I don’t think that sounds very like our tradition, so I think you should stop doing that.” And so he did. He gave up meditation, and he described later, after he’d come back to it, how this had been the beginning of a period off spiritually desert for him. But at the same time, his life was prayer, life and hurt. Your journey was being rich by with many other sources but something essential to his practice had been lost.

And many people, many people here will have had a similar experience. Discovering meditation, losing touch with it, giving it up for a year, a monthly and coming back to it, maybe giving it up again. The learning process for most of us, for me also, is not necessarily instantaneous. And John Main’s reconnection to meditation came at a difficult period in his own life when he was already a monk and ordained and headmaster of a large school. A very busy time of his life: his concern for his students and their spiritual crisis (this was in the late sixties) let him back to study and explore the roots of his own Christian monastic tradition of prayer.

The importance of the mantra

And it was there, in the teachings of John Cassian the Teacher of St Benedict writing on the 4th 5th centuries that he found teaching on meditation that he recognized because of his earlier experience. Essentially the same in terms of methodology, taking a word or a phrase and repeating it continuously during the time of the meditation. Saying it continuously, faithfully. At this moment he knew, he could see, he recognized he was at that moment where he was able to come to a deeper, more confident insight. He began to meditate again. And that’s why we’re here, in Squamish this week. Because his own rediscovery led him to the understanding that this needed to be shared. And that’s why we’re here, because of the community that has grown up to share this gift of meditation with the spiritual desert that we live in today.

So what the essentials of that tradition, that wisdom teaching on prayer that John Main passed on? That in the Christian tradition is called sometimes pure prayer or the prayer of the heart. And it leads to poverty of Spirit because, as we let go of our thoughts, our words and our imagination, even our good thoughts and our holy thoughts and our religious imagery, as we let go of it all. That’s the challenge to let go of all thoughts, words and imagination. Even the pious, even the most theological, even the most devotional at the time of meditation, we do what Jesus tells us to do in the Gospel ‘Leave everything behind’. That is the purpose of the word of the mantra, the sacred word: It is to enable us to come naturally over time, in God’s own timing, according to our own level of practice, to come to that poverty of Spirit which is the first of the Beatitudes happy of the poor in spirit.

People meditate not because it’s easy. No one said it is easy, it is simple, but not easy. People meditate for decades for their whole lives once they discovered it because it does lead them to this happiness. This kind of happiness that Jesus is speaking about.

Choosing the word that we say is important because we stay with the same word all the way through the meditation and from day to day. And this is why meditation is demanding, challenging. But if we understand why the tradition, the wisdom of this tradition teaches us this, then it’s much easier for us to get into it. Why should we say it continuously? Because we’re always letting go, letting go of the ego control, letting go of the desire, letting go of the fantasy letting go of our spiritual fantasy or are spiritually desire. Basically, as Jesus also said, in meditation, we’re leaving self behind. We do that in the most gentle way because it isn’t meant to be a violent path by saying the word faithfully and continuously.

So in our tradition, we could take the name Jesus: a very ancient Christian mantra. Or you could take the word Abba, for example. We recommend the word Maranatha. Maranatha is a sacred word in our Christian tradition. It’s in the language that Jesus spoke. It’s the oldest prayer St Paul Lens, the first letter to the Corinthians with it. So it’s embedded in the sacred tradition, but it’s also as a word, not in our own language. I don’t think anyone here speaks Aramaic fluently which means it doesn’t stimulate thought and imagination. It means Come Lord but we don’t think about the meaning of the word as we say it. Also, the sound of the word helps to calm the mind and the four syllables help you to say it. Most people say it in rhythm with their breathing.

You could, for example, say the mantra, the word as you breathe in Ma- ra- na – tha and breathe out in silence. But if you find that’s not comfortable, don’t worry. Many people would say the first two syllables Mara on the in-breath and na-tha on the out-breath. There’s no strict rule about it. Don’t get too self-conscious about it. Say it simply. Say it comfortably and you’ll find that you get into it fairly quickly. So that really is the essence of the tradition and the practice. What matters now is that we exercise that way, do it.

The importance of your posture

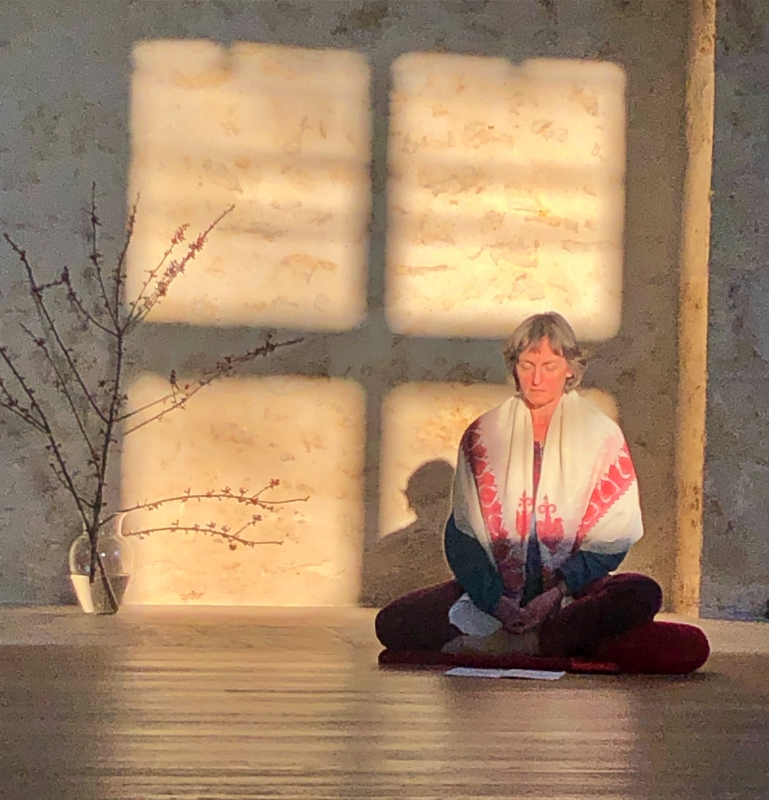

One final thing that’s important is posture. Meditation as the prayer of the heart means that is the prayer that touches and integrates and blesses in a way, the whole person. That’s the body, physical, the whole of our physical being. We are an incarnation, all faith. So we pray with the body, and meditation is a very incarnation all way of prayer. So for your posture, sit with your back straight, your feet on the ground. Relax your shoulders. Just take a few moments to settle in. If you to try to feel your sit bones as they make contact with the seat of the chair and align yourself on those so that you’re sitting upright, not rigid. But upright your shoulders relaxed and you can tuck in your chin in very slightly towards your chest, towards your heart, you could put your hands on your lap on your knees. Whatever is comfortable? You should be comfortable because we try to sit still on silent during the meditation means you’re trying not to make noise. Is that interrupt the silence for other people or for ourselves? So it’s a good idea to clear your throat or blow your nose or whatever you want to do before meditation.

So just relax into that posture, which is both alert and comfortable and just and close your eyes lightly for a moment. Be aware of your breath, John Main said: “Meditation is as natural to the Spirit as breathing is to the body.”

“Meditation is as natural to the Spirit as breathing is to the body.”

You just feel the breath coming into your body, refreshing and revitalizing you with the gift of life. And because it is a gift you could never possess it. So let it go. Breathe out, let go. So every breath we take is a source of wisdom. It teaches us the art of living. Meditation is a way we accept the gift of our being. Just be aware of the breath coming in and flowing out and then gently but clearly introduce your word and begin to articulate it in your mind and heart and listen to it. The word again, I suggest, is Maranatha. Four syllables Ma-ra-na-tha and listen to the word. Don’t visualize it, but listen to it.

Give it your full attention. Say it gently without force. And when you get distracted, which is about every one half of a second, let go of the thought, let go of the image, let go of the distraction and humbly return to your word Ma-ra-na-tha.”

Sources of Wisdom

This is talk one of Sources of Wisdom, an online retreat on essential teaching of meditation provided by The School of Meditation. The time of self-isolating and social distance that we are currently experiencing is a kind of extended Lent: a voluntary restriction which reminds us of the limited control we have in reality – at any time – over the circumstances of our daily lives. A willing and conscious entering into these limitations can, paradoxically, bring us to an unexpected experience of limitless freedom. This is also how a retreat will work. Another way of thinking of our new collective social reality is that we are undertaking an enormous global retreat. Some are following it more attentively than others; some are quite unaware that they are on this retreat, but more and more are quieting down and joining in. Given that most of our communication and exploration is – for the moment – online, what better time to take part in an online retreat? You can learn more about this retreat and register here.