Dearest Friends

Perhaps like many others in recent times I have felt tempted to disconnect from the daily news. I can understand the friend who told me he does not follow the news at all anymore giving all his time to his family, his work and his inner life. I asked him wouldn’t he like to know if there was a new government or world peace had broken out. He said he would hear it from people at work.

I can sympathise but I wasn’t and am not convinced by this. I understand the effect of the continuous sadness, anger and frustration resulting from unwise or even malevolent global and national governance. There is a depressing vacuum in the new kind of leadership we need to navigate the forces of change disrupting our world.

As the desert father once said: “the time will come when the world goes mad and the mad people will look at a sane person and say ‘he is mad because he is not like us.’ ” In a time when truth is trounced and real news is called fake news and so all news is suspect, it is easy to feel powerless and hopeless. But unrestrained, this mood leads straight into what the desert fathers called acedia, a deenergised state, a dark night when it seems the dawn will never come and where giving-up replaces letting-go. In Harry Potter’s universe the ‘dementors’, foul, wraith-like creatures that feed on human happiness bring about this state in their victims. To get too close to them is to be drained of life and hope and be left with nothing but your worst memories.

So why keep up with the bad news?

Why not eat, drink, be merry, play in the sun and fulfil only our most immediate responsibilities? The reason I haven’t succumbed to the temptation (though now I get my news from better sources) is twofold. Firstly, even if the reality is that the powers of unreality are mastering the world, we have a duty to face that reality and to keep paying attention to the good that still exists in the world and indeed in everyone, even the worst of leaders. Secondly, we need to face the whole truth and fulfil all our responsibilities if we are to contribute to what we are each indissolubly part of. We belong to the world as we belong to a family, like it or not.

To be at all is to be with. The Self is distinct from the Ego because in the consciousness of the Self we see how we are connected to everything within a great unity of the web of being. The Ego falsely claims it exists outside everything except its own admirers or dependents, always an ‘objective’ observer, ever pursuing its particular objectives and self-interest. This disastrous self-deception illusion leads eventually to loneliness in the most desperate degree.

In reality, the deeper our solitude the stronger is our sense of connection, of inter-dependence – and consequently of personal and social responsibility. This was the point I was making in the talks at the Monte Oliveto retreat last month: that loneliness is a failed solitude and solitude is the acceptance of our uniqueness. Only in solitude can we truly love and know how to give our self.

The spiritual path is not merely a part of life for which we have to find time. Life is the spiritual path. Sometimes, though infrequently, a serious spiritual practice like meditation leads to a special and frightening kind of interior crisis. In it we are faced with a perception of the universe as being nothing more than what it is, what we see, how it works. Expressed like this it seems to have a harmless, even peaceful is-ness. We can see the world as it is, without the usual filters. But at times the angle of this perception shows us a universe with no meaning other than its own eternal, cyclical existence. It may be vast and wondrous but its lack of depth and meaning or of any personal connection is terrible.

Any crisis in life – of loss, transition or fear of death – could trigger this. It can also come on suddenly, unannounced. Then it is the crisis. At first, it can expose an unfathomable feeling of isolation. It seems that nothing but our own rationality can help us. But rationality – our ability to analyse and explain things – is easily overpowered by the brute force of this revelation. The best advice from the wisest sources is ‘don’t fight it’. In fact we need to allow failure, to permit all our defences, all our bolt-holes, all our false consolations to be overwhelmed by this wave of reality surging towards us. ‘It is a terrible thing to fall into the hands of the living God’.

It will seem as if – if God exists at all – that God is nothing but the infinite “I Am”, an Ego of unimaginable magnitude and indifference to others, including its own creation. Many mystics have reported on this experience. Because they face it and don’t trivialise it, their value to us today in developing a contemplative response to the crisis of change (the theme of our Seminar in September) is invaluable.

They describe it honestly because they have discovered the self-transforming truth that glows at the deep heart of it. Perhaps we will all pass through this experience (hopefully briefly) at the moment of death or during our preparation for death. The sure hope in the face of this unavoidable darkness is that there is always something next. Embracing that inevitability creates the hope on which all human effort and society itself depends. Hope empowers us to let go. Once we are in the letting-go mode of consciousness, rather than stuck in the clinging mode, the boundless cosmic solitude in which all attachments are dissolved can unfold fully. Something next. Something comes after the perception of the bare mechanics of the universe. We find ourselves to be in the great I Am, not outside it. We are found there, confident at last that only illusion exists outside of it. This at least is not fake news.

Our urgent responsibility today, each of us, is to find the particular way in which we can experience this truth and be carriers of the good news it enshrines. We don’t do this as individual messiahs but as disciples in community. Even Jesus claimed that his authority was not his own but flowed directly from the source, from the I Am. He formed and empowered a community that is still growing. It is still imperfectly trying to discover in each person and in each generation what he meant. As meditation teaches us imperfection does not harm us. Infidelity does.

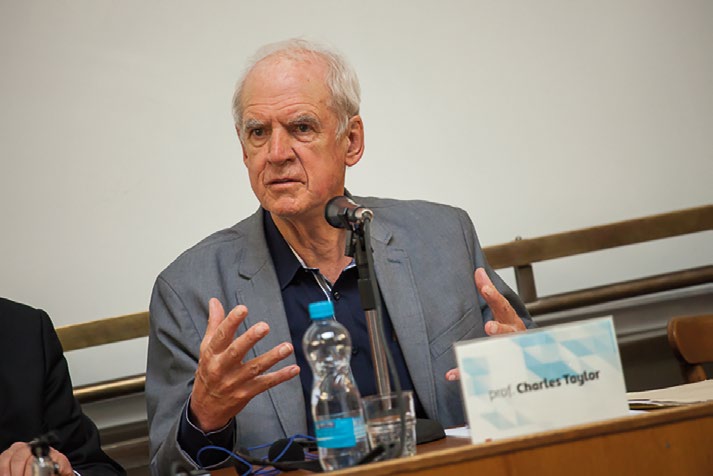

All of this explains the John Main Seminar this year, hosted by our Belgian community in the contemplative city of Bruges, near the beautiful Beguinage where medieval laywomen once asserted their right to a spiritual life free from oppression and patriarchal control. The Seminar will bring together contemplative minds from diverse fields – politics, religion, medicine, economics, education, science, philosophy. The contributors are men and women of standing and deep knowledge in their areas of expertise. They will reflect on the great forces of change affecting their specialised areas. But we will also seek a synthesis and understanding of the common patterns within the crises of change, especially with the help of Charles Taylor’s comprehensive mind.

Change is always disturbing especially when we cannot predict or control it. Not much can be managed or outsourced for long. We need toexperience the paradox that enlightenment is taking responsibility and realising that we can never be in total control. Another paradox helps: sometimes we need to become empty to see the fullness, to be alone in order to see where we belong. The Sufi poet Rumi describes this in his poem ‘Acts of Helplessness’ written when ‘you cry through the night and get up at dawn, asking, that in the absence of what you ask for your day gets dark’. He describes the dark night of unfulfilled days ‘when acts of helplessness become habitual’. And he sees that those very acts are the signs we need to find direction. ‘Excuse my wandering,’ he says at the end of the poem, but ‘how can one be orderly with this? It’s like counting leaves in a garden’. He ends: ‘sometimes organisation and computation become absurd.’

Nevertheless it is important that we think – and think clearly – about the challenges pounding us. This is why, in the Seminar this year, we are bringing great minds together with meditation that we believe will open the way forward for our so often confused and self-destructive world. We will not claim that meditation will solve all our problems. Maybe it would if we all tried it. But, as that won’t happen, we need to see meditation not as a problem-solver but as an ‘habitual act of helplessness’. Only those, who do it, really know how it changes them, by clarifying their minds and by opening their hearts day by day in whatever field it is their destiny to inhabit.

At the Monte Oliveto retreat we explored the paradoxical human destiny of ‘being alone together’. Failing to live into this paradox, we slip into the epidemic of loneliness and disassociation that is sweeping through the affluent world today. It is sobering to ask why Haiti has the lowest suicide rate in the western hemisphere while our over-satiated consumer societies are witnessing a dramatic rise in suicide especially among the young. In reaction to this dilemma, we are becoming an increasingly therapeutic society – often to a degree that inhibits our being able to create or to celebrate. While we can be pleased at the progress in being able to admit our personal problems and to care for them, the danger is growing that we become collectively fixated on our individual unhappiness.

Perhaps it began with the Declaration of Independence and the assertion of the inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. At times, when under oppression or in a crisis in our development, this does need to be declared. But what happens when we have become independent, self-determining, when our parents have become dependent on us, when freedom to act as we wish is found to be far more limited than we had imagined and when the happiness we are pursuing comes to seem and self-destructive world. We will not claim that meditation will solve all more a duty we are failing in than a right we actually enjoy? Love is all we need. Not the primitive stage of love where we seek ourselves. But the full-blown love in which we contemplate the other and care for their well-being more than for our own. At what turning point in the human journey do we see happiness in terms of others rather than just ourselves?

The greatest spiritual teachers call us not just to ‘follow’ them but to be their disciples – to learn from them. Only in the depth of personal relationship, the frightening full intimacy of discipleship, of the love that few dare to risk, can we learn how to re-centre our selves. The gravitational pull of ego-consciousness often seems irresistible. It is as if it can only be temporarily transcended before we sink back into self-centredness, seeking our own happiness, endlessly asking why we haven’t found it yet. We feel helpless. But we are still reluctant to exercise those ‘acts of helplessness’ that would actually turn things around. The great teachers of the wisdom traditions teach us that in the worst crisis of change, however hopeless or uncontrollable it seems, our meditation, those contemplative acts of helplessness, are the best means available to let go and keep moving forward.

Jesus does not call us not to pursue personal happiness directly. We trample over too many others if we and self-destructive world. We will not claim that meditation will solve all more a duty we are failing in than a do that. Instead, we are invited to attend to the needs of others in order to find the true happiness of the Self that so far transcends that of the ego. But how can I help others when I have so little myself?

“Here is a boy with five small barley loaves and two small fish, but how far will they go among so many?”, Peter asked at the feeding of the multitude. As the individuals in the crowd started to re-distribute what they had with each other, he discovered the miracle of transformation released by sharing. In a time of change, when we tend to retain our resources in self-protectionism, this truth, not some external magic or mastery of events, is the redemptive wisdom.

Mahayana Buddhism reflects this, too, in the idea of the bodhisattva way of life. We looked at this teaching over the days at Monte Oliveto. It begins with a desire to awaken the mind to truth but it then requires that we actually practice it. It is like the transition from wanting to meditate to actually learning to meditate. However often and badly we fail, the faithful commitment will lead us home. In pursuing our own happiness we undermine whatever happiness we have. But by seeing ourselves as ‘medicine for the sick’ and determining to reduce the suffering of others as a first priority we can stare down the forces of denial and despair which arise from the self-centred mind. These dark doubts are then exposed as ‘weaklings to be subdued by wisdom’s gaze’. As ever, we find our true strength in embracing our actual weakness.

Speaking about the teaching and living the teaching are not the same thing. In our Bonnevaux vision we are risking to live it; and it is teaching me something about the mystery of change. Looking back to some of the turning points in our community, our move to Montreal, the death of Father John, the transition from Montreal (where I am writing this today on my birthday) to the World Community and its many transitions over the past twenty-five years, there are a lot of changes to learn from. The question, in the crisis of change, is not only ‘how do we get through this?’ but ‘what next?’

There is always something next. Even when we do nothing, there is something next. Often if, from fear or denial, we do nothing what comes next is harmful. If, from hubris or impatience, we do too much it can be harmful too. So what we do needs to be measured.

Bonnevaux is the next thing for us. It is our way to align with the force of change that our community, by serving its mission, must face. As I visit Bonnevaux regularly – early next year I will move there permanently – I have seen more clearly why we have been led there. Our ‘monastery without walls’ does not need centralisation but it needs a physical centre for it to grow, for a new generation of teachers of meditation to be nurtured, for pilgrims to come and find a stepping stone to the next level of their journey, for the institutions and professions of the world to encounter the contemplative consciousness they have lost. And, anyway, who does not need a home?

Stability in the right kind of centre is the best condition for growth. The right kind of physical centre is whatever best reflects the true centre, which is the heart. You know that you are in touch with the heart when you can face reality with the minimum of fear and the highest level of love, seeing the world not only in its darkness but as also bathed in the light of truth, of beauty and of simple human kindness. The best solutions to problems arise from this simplicity of perception.

“However often and badly we fail, the faithful commitment will lead us home”

So, Bonnevaux represents a big change for the World Community but also a way for us all to learn how to deal with change in the best and most humane way. It began and continues as a work of faith, our being faithful to the story so far and so to the next thing. In terms of people, finances and everything else, I must tell you there are no absolute certainties. That means the fulfilment of the Bonnevaux potential will depend upon the faith that others, new and old, friends and members of the community, will tangibly put into it: time, talent and treasure.

I feel this to be a powerful affirmation of its rightness. So far, at each turn there has been a touch of grace, an unexpected gift, the passing tip of an angel’s wing. Two of our core community at Bonnevaux, whom I thanked for their sacrifice in giving up so much to serve it. They said they didn’t look on it as a sacrifice but as a privilege. The young volunteer who had never meditated before but who came for three weeks and immersed herself in the rhythm of the daily life and has been meditating since she left. The architects who come and meditate with us in between the technical meetings. The workmen who do not play radios on the building site in order to maintain the spirit of silence. The French community who have formed five skilled working committees to cover different aspects of the project. The visitors from many parts of the world who have visited and stayed on site or nearby in order to share and support the daily building-up of this new centre and home – that we hope will become a small working model of how life can be lived in the crisis of our times.

Thank you for keeping Bonnevaux in your hearts and intentions so that our community can change and change for the better for generations to come, long after the global crisis we are facing today has been navigated and humanity faces new and more hopeful possibilities.

With much love,