Dearest friends,

A top diplomat recently wrote a kind note of support for Bonnevaux and began by saying in a rather undiplomatic way, ‘the world is in a mess’. He added that the need has never been greater for centres of clarity, inclusivity and peace such as we pray Bonnevaux will be with God’s help (and yours). The contemplative life has often been misrepresented down the centuries. It has been presented as an option, often a very selfish choice, for a private peace and seclusion, an escape from the world and its problems. Many people, avoiding the work of silence for themselves but caught up in the affrays of the world saw centres of contemplation as dream get-aways.

But, if we see contemplation as a way of living in the present, with minds and hearts wide-open in rationality and compassion, the truth is very different. The contemplative life is ordinary, as ordinary as our own frequent faults and failings, and as our innate commitment to hope and to a more peaceful and fairer world. As ordinary, in other words, when all the layers of sentimentality and commercialism have been extracted from our understanding of its radical, universal meaning, as the birth of Jesus.

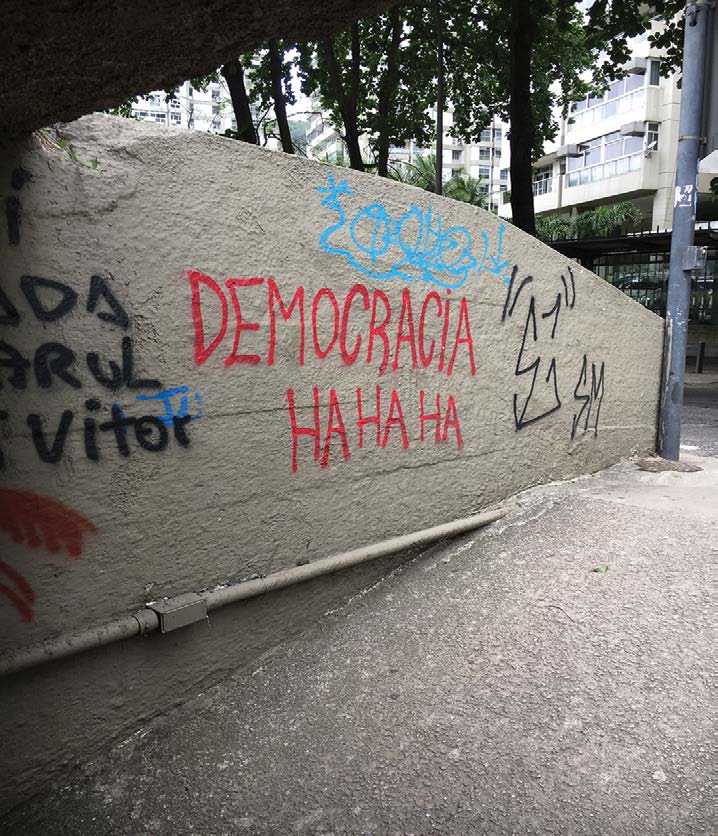

The incarnation is the greatest of revelations wrapped up in the simplest of packaging. It illuminates not the institutional, but the heart’s meaning of contemplation, the vision of God rather than the observation of God, seeing not looking at. It shows anyone who beholds it that the human journey is the evolution of each person, whatever their gifts or background, towards a state that is, simply, divine. ‘God became human so that human beings might become God’ sang all the major Christian teachers before the caste-system returned and power-structures obscured the truth that blazed out in Bethlehem. Not only diplomats today feel the world is in trouble. ‘Democracy ha-haha’. as the hurting graffiti in a Brazilian subway, pictured on the cover, declared, is hard to define and today harder for many to believe in. It depends on a delicate balance of force. It requires levels of self-restraint and civility that make it is easy to hijack by populists, cynics and fools. A referendum today, therefore, seems a particularly volatile cocktail for democratic process. To redress a balance that is so imperilled we need more than platitudes and surface change. A more radical and costly change of attitude, such as Pope Francis has initiated in the Catholic Church is demanded by our times.

A friend in the financial world wrote to me after the election, reflecting on all the instability and sadness in the world, that ‘there are simply too many people that have not participated in the brave new world we have created.’ By ‘we’ I think he meant all of us who have a degree of comfort and privilege compared with those struggling to survive war and emigration or to feed their families in the dismal parts of our cities. In particular, I think he meant those charged with responsibility for the big decisions about money and power. Their decisions have doubtlessly made the world a wealthier place. But they are also driving an ever widening wedge between those who have absurdly too much and those who have barely enough. Jesus said the ‘poor you will always have with you’. It is the gap between the poor and the rich, above all, that makes for the tragic mess.

How does contemplation, awakened through meditation, the work of silence, help us redress the balance that is the foundation of the virtues, of justice, peace, health and happiness? How can we teach and share this gift that is free and must remain as free as a bridge of impeccable trust?

Meditation is the simplest and most universal means of awakening the contemplative mind and thus raising the level of wisdom in the world. Acting with an unbalanced view of things, however, we can turn an ancient source of wisdom into just another component, a fad or a product, of our technoculture. However many the miracles and conveniences that science has showered on us and even though it can crudely devalue the human and blur the identity of the human and the machine, it cannot replace the human. The human is the process of change through which the divine most fully incarnates. God becomes human, not a system or a computer. Meditation, then, is always better understood as relationship not as technique. It is more like marriage or monastic vows or any sincere way of life than a course or an app.

After the novelty of the practice has worn off, and if the discipline begins to take root, the times of meditation become naturally woven into daily life. It all becomes natural and ordinary. But it also becomes transfiguring, a constant agent of change that reveals the depth dimension in everything as soon as it opens and integrates the subtler levels of our selves. As one begins this journey a hard but necessary thing to be reminded of is that it is not like any other experience we are familiar with. It is in about letting go rather than grasping – something particularly hard and counter-cultural today for the busy malls of our minds to see. At the end of his life, the Buddha was asked what he had got out of meditation. He replied ‘Nothing… But I have lost a lot.’ Jesus too emphasized that we cannot find without losing and that discipleship, the most fully incarnate form of the human relationship with the divine, requires that we abandon ‘all your possessions’.

If only it were an experience like others. It would be easier to sell and to master. But then it would not propel us forwards in the direction that our lives naturally seek and need to follow. The experience of meditation is that of an ever deepening, self-renewing relationship. When one thinks it is exhausted it turns and takes on a new lease of life.

John Main famously said, ‘nothing happens in meditation and if it does, ignore it.’ Perhaps not the best way to sell something, but the truest way to lead people to start and continue on this way of grace. What he means, of course, is what the contemplative wisdom has always taught. Experience, as we usually understand it, is already something past, a snapshot or concept of something we underwent without knowing what it was just because we were so fully involved in it. There was no bit of us standing on the sideline recording and evaluating. We were, it is true, in the experience, but the experience was not compartmentalized in us. The description, even the meaning, comes later because experience is only a vestige in memory. Our hunger for experience and of course for novelty and the prestige related to it, runs counter to the whole meaning of contemplation. Understanding this, John Main said that the ‘most important meaning for modern people to rediscover is that of silence’.

Sadly, this is not what the church has taught in recent times. It has marketed the supernatural, the extraordinary and ‘experiences of grace’ because there will always be a market for this kind of thing and for other less service-oriented reasons. But this exhausts the genuine religious spirit and leaves it dependent on images not reality, on the surface not the real depths of God. It is also abstract, intangible except in the imagination, and falsely incarnational.

“Silence is truthful. Nothing is more important for us in our post-truth world of ‘fake news’ and manipulative mass deception than to remember what truth really is”

If, in the early days of meditating, we can find the help we need to strengthen our practice to withstand these initial challenges and to control our craving for experience, we will soon discover the real work and the wonder of silence.

Silence is creative, refreshing, healing and de-toxifying. It can seem at first, however, as if it were negative and so frightening. To be truly silent, it seems, must mean to disappear altogether. But when we see that silence is reached through the work of pure attention, not on an object of attention, we have breakthrough. We fall into seeing how contemplation is indeed the expanding experience of love. Everything we have called love before is re-mapped. In this we are swept above our small self-consciousness and increasingly, in the bigger picture, the truth appears.

Silence is truthful. Nothing is more important for us in our post-truth world of ‘fake news’ and manipulative mass deception than to remember what truth really is. Merton once said that ‘I make monastic silence a protest against the lies of politicians, propagandists and agitators’. This is true and Bonnevaux will be part of this ancient monastic protest of truth. But today we have to see that the monastic is related not only to monasteries but to the monk within all of us, that part of us which ‘truly seeks God’ and knows that solitude is the condition of real relationship. A community, familial, monastic or global, is as strong as all the solitudes which compose it.

To the mind addicted to noise and novelty, silence will seem like a negative emptiness. In truth it is an emptiness filled with the degree of potential that matches the level of silence attained. Ultimately, until we fall beyond boundaries, into an ‘order without order’, into the freedom that is the life of Spirit, the silence that is God. Meister Eckhart describes this, in the mystical language of paradox, when he said.

In contemplation we become pregnant with nothing and in the nothing God is born. God begets His Son in our soul. God begets me as His Son.

To be human is to change. As contemplative consciousness grows it is our very way of perception that changes. It is not that we become ‘better at meditation’ but that we see that real ‘experience’ unfolds not merely as something we observe or feel during the meditation but through all the dimensions and in every nook and cranny of life. In everything, we become more committed, less doubtful. Faith, not will-power, takes over and surprises us by the way it moves mountains, often at first by reducing them to little hills. Mystery then emerges from the ordinary rather than dramatically descending from the rafters above. Our idea of God (whether we are believers or agnostics) will also change and with it our whole set of our beliefs and values. God becomes more manifested by our discovering meaning through an expanding sense of connection to those around us, including those opposing us and those who live in other worlds, off the radar of our comfortable zones. In all these ways contemplation grows into action and political courage.

Today we feel understandably frightened by the speed of change. We can hardly adapt to the new before it is superseded by the arrival of next disruptive thing. We feel we are losing control and swayed by fear we rashly run after those we wrongly think can control things better. The catalyst of good change – change that moves us towards the human goal – is in fact at first interior not external. External changes are passing states. Interior change happens definitively as self-knowledge develops. As with the meaning of ‘experience’, the contemplative understanding of self-knowledge sees important distinctions regarding self-knowledge. It is not essentially just what we know about ourselves or how we think of ourselves – self-confidence or self-doubt, for example – but that we are ourselves in the deepest and non-self-reflective silence. It is not what we learn about ourselves through magazines. It is what we lose and find in our solitude.

This kind of self-knowledge cannot be put into ordinary words or concepts. It is seen at work in its effects, the changes it works on our lives. When we are truly still and the grip of the ego is loosened, things change as they are meant to change. A kind of knowledge that we have never perhaps known before rises up gently, and yet, as in the story of Elijah’s encounter with divinity on the mountain, with a quietness and modesty stronger than the earthquake or the storm.

“To be human is to change. As contemplative consciousness grows it is our very way of perception that changes”

Discovering this kind of knowledge as true power, this kind of change as the healthiest, we reclaim one of the casualties of modernity, the wisdom of stillness. Hesychia. St John Climacus almost sounds like a modern business consultant selling mindfulness when he speaks about ‘hesychia (as) accurate knowledge and management of one’s thoughts. Stillness of soul is science of thought and a pure mind. Brave and determined thinking is a friend of stillness. It keeps constant vigil at the door of the heart.’ Clearly, then, meditation has benefits for the mind. There is nothing anti-intellectual about laying aside one’s thoughts or leading the mind into or enter the heart through the path of stillness. The fear that stillness spells death soon evaporates and we discover instead a whole new range and brilliance of life. All organisations, democracy included, work better when people have clearer and calmer minds and are able to tell the difference between fake news and the simple truth.

Walking Jesus’ ‘narrow little path that leads to life’, the Buddha’s ‘middle way’. or St Benedict’s ‘nothing in excess’, requires balance. The balance of moderation demands vigilance to avoid falling into extremism. Moderation may make for less exciting news items, but it is in fact more thrilling because it awakens the senses and the intelligence on higher levels. It avoids dullness and enhances enjoyment of the truth. In the business world, ‘stability’ is seen as necessary for investment and productivity. Usually this means no more than’ peace as the world gives it’, provisional and easily upset short-term solutions. The peace of Christ, however, arises from the heart of reality not from its surface weather patterns. A conscious contact (not just a self-conscious experience) is necessary to transmit this peace into the human, from the heart itself. Politics, business or religion, without heart are unable to make the world a better place.

We all desire change, but on our own terms. Our image of what we want to change is limited by what we desire. We become no more than creatures of desire. And so, it binds us to suffering, sadness and suffering, products of the cycle of desire, satisfaction and disappointment. It traps us in a realm of images and abstractions. The problem, in restricting change to what we desire, is desire itself. We never desire enough. The feast of the Epiphany reminds us how the whole potential, the glory of human destiny, is manifested in the person of Jesus and now through the cosmos in the body of Christ. Glory is always eager to burst through the ordinary things of life and allow us, even within our present limitations, to see the world as a paradise.

Meditation works by transfiguring desire: at first through those twice-daily periods where we commit ourselves wholeheartedly to poverty of spirit in the renunciation of desire. Increasingly, as change takes deeper root in us, we see how desire is changed in all areas. What and how we desire are no longer blindly controlled by illusion. Eventually we come to understand what the mystics really meant when they said we should desire only God. At first this might seem an embittered rejection of the world and all its beautiful ways of manifesting the divine. Religious people who lack heart jump onto this language and twist it in order to repress and control the natural desires and joy of life. But once the process of transfiguration is underway we see what it truly means. To desire only God means to resonate in harmony with everything that is real.

Change is the only thing that doesn’t change. In the heart of God we find our deepest sense of belonging and transcend our self-consciousness. This is eternal change (the meaning of ‘eternal life’) and becomes the eternal now, the stillness in which the divine self-knowledge of love emerges and changes us. In the I Ching, the Chinese ‘Book of Changes’, wisdom is the ability to recognise where at any one moment we are in the perpetual cycle of change. In hexagram 20 on contemplation this is shown leading cyclically into the mystery of reality, just as every birth leads to an endless series of changes and experiences. In this Chinese wisdom text, contemplation is described as the space ‘between the ablution and the offering’. Similarly in the Latin word contemplatio, templum refers not to the building structure but to the space in which it is erected. I think this is why when people come to Bonnevaux it is not just the building but the space in which it floats that reveals itself to them as an entry into contemplation and peace.

If the way home in this space is so simple and evident, why do so few seem to choose it? Life is continuous choice, often between the lesser of two evils as in democratic elections. But we are always facing a choice between right and wrong, the best life-partner, a new password or career. Too many choices create anxiety. Choices that only we can make often make us feel lonely. No doubt this is why, as our world fills up with choice and complexity, a complementary hunger for simplicity arises. We look instead for an economy of effort, the place of the choiceless choice where we give our assent rather than pick one option. But why do some people want to meditate and others don’t? Why do those who want to meditate have to compete with part of themselves that resists it?

Maybe it is because we assume that it is only, or even primarily, about ourselves choosing. Yet: ‘you did not choose me. I chose you’, Jesus tells us. He adds that his choice is so that we can go out and bear lasting fruit – not just experiences that come and go but a continuous transfiguration that truly begins when we ourselves have begun to incarnate. The knowledge of being chosen unsettles us. It threatens our ego-control and often forces us into a combative relationship with whoever we feel is doing the choosing. But by learning (through discipline) and allowing (through letting go) the contemplative way of seeing we realise that to be chosen and to consent to it is the greatest freedom.

Aquinas said that what is new about the New Testament is the grace of the Holy Spirit operating in the heart. We don’t choose this but we say yes to it. To say yes is partly a choice but mainly an act of faith in which we surrender ourselves into an absolute equality. Isn’t this what we celebrate God doing with us in Bethlehem? If we see it in a contemplative light we have found the key to our present dilemma. We have found the wisdom way of radical simplicity. We learn over time how to celebrate diversity rather than fear strangers and how to mingle rather than separate. Contemplation is necessary for our next step of evolution.

All of us who serve the community on our international team join me in wishing you, and all those you serve, a happy and holy season of the Lord’s birth and epiphany. Please keep Bonnevaux in your heart in a special way as a future place of contemplation and unity to serve what I have been trying to describe in this letter; we pray we will be able to welcome you there one day.

With much love