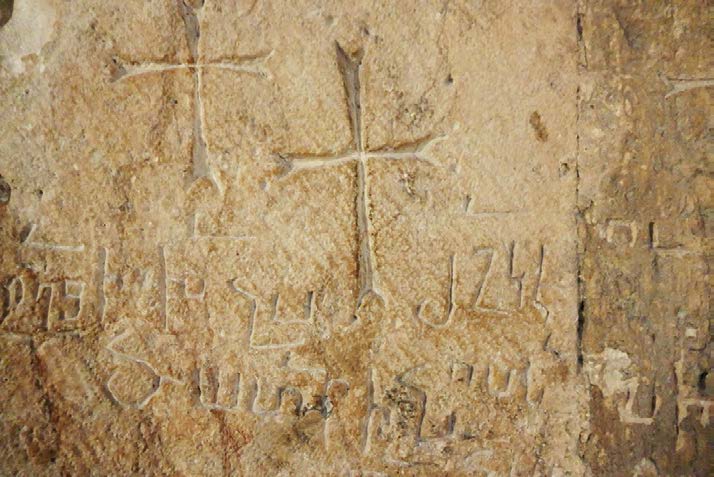

During our WCCM Pilgrimage to Israel last month we visited the city that the gospels call ‘Jesus’ own city’, Capernaum. Born in Bethlehem, raised in Nazareth, once he began his teaching and travelling mission, he moved his base of operation to Capernaum on the north-east shore of the Sea of Galilee. Now it is an archaeological site but then it was an international highway connecting with the wider world. Here, he spoke regularly on the sabbath, called his disciples and healed people. From the fifth century a church existed on the traditional site of Peter’s house – perhaps the 1st century house whose foundations we visited and where Jesus came (Mt 8:14) to heal Peter’s mother-in-law. Perhaps (many perhapses) it was where Jesus made his home whenever he came back to Capernaum.

Such ideas are probabilities at best. But it is moving as well as enlightening to stand there, realising that it was here (or somewhere very like it) that Jesus of Nazareth was also Jesus of Capernaum, a short distance from the Jordan where he was baptised and from the level field on the mountainside where he gave his great Sermon. It is moving because it brings home to us the historical, human reality of the

Word made flesh. (I am writing this on the Feast of the Annunciation). The cosmic Christ was once a local Jesus. It is enlightening because it opens us – or, at least, it made me feel – how the dimensions of time and space we inhabit are only some of the many dimensions that constitute reality. General Relativity says we live in three dimensions of space and one of time. String Theory thinks there may be up to twenty six other dimensions. Space and time may be merely ‘curled’ up, they say, in other dimensions on a subatomic scale.

So, (I won’t say ‘perhaps’ any more), once a local always a local. Jesus of Capernaum like each of us, is local and global, historical and timeless. In geography every location on the earth is unique and at the same time similar to all other locations. In physics a point does not have dimensional attributes: it is a

‘unique location’. I don’t understand this, but it can help at least to begin to understand the mystery of Christ. This mystery is the experience of the Resurrection. We need examples, symbols, analogies, sacraments, to help us see that contradictions can co-exist, like the two sides of a coin. We cannot approach any mystery without being confused at first. Remember the first time you meditated and what you thought about it afterwards? If you have lost someone you loved, remember how you became aware that the love did not die but continues to grow?

Pilgrimage to our own religious sacred sites and to those of other faiths helps ground us in a spiritual

mystery enfolded in time and space. Meditation is the interior aspect of this pilgrimage. It can be practiced within the house of our own faith, alone or with guests. The guests may then invite us to their homes to meditate with them there. By meditating together, we open to the all inclusive spiritual dimension of reality. We recognise it because it heals divisions and engenders love.

When I was a boy studying history at school, we learned that a clever sounding way to start an essay was ‘XXX was a time of transition’. We were reminded by our teacher that every age is transitional. Nevertheless, today, we are all acutely conscious of being a transitional generation in almost every aspect of life. When we see how rapidly change is happening around us, we call it a ‘time of crisis’. Then, interiorly, we can feel at a loss, caught up in its rush and confusion. Language then falters and fails us. We use extreme terms – crisis, cliff-edge, danger, disaster – for almost everything. The media thrive on the ‘breaking news’ and ‘live feeds’ of extreme events. In such a world, it’s more than ever

important to be aware of the multiple dimensions of reality and not identify only with what we can see

and touch in our comfort zone. Regardless of religious belief, we need the spiritual dimension that enfolds all dimensions. And this is why a contemplative mind is necessary to survive and navigate modern life. And why, if we are truly concerned for the next generation, we need to make meditation integral to our children’s early formation and education.

Religiously, the crisis is as acute as in all the social and ecological aspects of our world. Religion has largely failed to connect with the spiritual needs of people. Christianity is widely dismissed as a retrosexual morality – attended by the hypocritical embarrassments that carries. A spiritual black hole has opened in our consumer culture and our institutions. Because of all this, the spiritual dimension, that enfolds and connects all dimensions of reality, is often hijacked by reductionistic techniques that soon become new forms of superstition and magic or just more packages in the commercial market-place. The old gods are dying. New gods are ascending and replacing them.

‘gods’ depend on the worship, enduring belief and sacrifices of their devotees. They (and their representatives) get their power from the people. Socrates saw this long ago, when he understood the meaning of myth and the natural basis of the gods. He paid the price of rejection for telling what he saw. While the old gods are strong, they and their supporters can be brutal. But, when belief and devotion move away from them, the old gods – old religious systems and rituals – weaken. They struggle for numbers. Yet, it is hard to live without gods. There is a non-materialistic side of humanity that demands expression, symbolism and seeks meaning. ‘gods’ help us satisfy this, however superficially – the pantheon of media celebrities, frenetic shopping centres running their devotees into debt they cannot afford, the gods of war and misinformation and drugs. The old gods – religious devotion, consecrated life, the mystique of celibacy, the power of priesthood, Sunday worship – find it hard to compete.

“A cyclical pilgrimage into the dimension of reality that the Resurrection has opened for humanity…”

Religion and culture are woven together. When one evolves so must the other. Otherwise they split and we feel increasingly disconnected. Of course, we are more than our cultural conditioning. So, the life of spirit still teaches and touches us: when we fall in love, when we fall out of love, when we fall sick, when we briefly enjoy physical perfection, when we give birth, when we sit by a death-bed. But increasingly, daily life, however affluent, looks like a wasteland even to the young who normally see things with hope and optimism. The dimensions of time and space themselves are filled with stress, psychological suffering and the feeling of entrapment. We can try to escape because there is no lack of escape routes in fantasy, distraction, addiction and other ways of self-harm.

We need another kind of wasteland, a desert, to find our way back to the sense of wonder in the multidimensionality of reality. ‘Oh, what a beautiful world’. We can then find our unique point of location, where we belong and where we know who we are because we are known. There are no ‘gods’ in the desert, just our own demons and the angels we need.. There is only the God who is and who has no name.

We need another kind of wasteland, a desert, to find our way back to the sense of wonder in the multidimensionality of reality. ‘Oh, what a beautiful world’. We can then find our unique point of location, where we belong and where we know who we are because we are known. There are no ‘gods’ in the desert, just our own demons and the angels we need.. There is only the God who is and who has no name.

Jesus spent his Lent in the Judean wilderness. He practiced selfrestraint and dealt with the demons we all know. He knew the seeds of pride, greed and self-fixation in the human psyche. We should never be complacent about having fully mastered them. It was after his time in the desert of self-preparation that he settled in Capernaum and his voice began to be widely heard. Our own forty days are similar – a time of self-restraint to repair some of our obscured spiritual vision – giving up something and doing something extra. Undertaken seriously, we soon feel how this purifies, focuses, our whole way of seeing and acting.

‘In Lent we are preparing to celebrate Easter.’ This sounds trite, unless we understand what celebration means. It is more than ringing bells, eating chocolate and smiling. It means that the dimension in which the Resurrection of Jesus is experienced is opened wide. We no longer look at it from the outside. We see ourselves within it as a dimension of Jesus of Capernaum giving us direct access to the hidden dimensions of reality. In a strange way this is so for believers and non-believers. To believe is a wonderful asset. Those who have it like to share with others. But what matters even more than belief, is faith, which is our deepest capacity to relate to reality. We can share the benefits of what we believe with those who don’t, provided we can meet in the experience of faith – the experience beyond words and thoughts that we find in meditation.

Lent prepares us to celebrate the Easter mysteries more deeply each year; it is more than a liturgical celebration. It is a cyclical pilgrimage, deeper into the dimension of reality that the Resurrection has opened for humanity across all dimensions, backwards and forwards in time; and in every unique location, the West Bank of the Palestinian territories, and Christchurch, New Zealand, Bonnevaux and your own home town. In the desert we tried to purify the doors of perception. We wanted to be more open to the dimension that enfolds every dimension. Our effort, like our daily meditation, is a sign of good faith relating to what we cannot see or prove or understand. But which we come to know. When we look back over Lent and evaluate what we did or didn’t succeed in, we should not evaluate it falsely. It is not about how perfectly we kept it but how far we advanced in self-knowledge. Perfectionism is a false light manufactured by the ego. Self-knowledge is the light of our spirit illuminating all dimensions of reality.

‘Dimensions of reality’ sounds very abstract. But they refer to levels of experience. Meditation, as John Main often said, is about experience not theory. Anyone can enter this experience, even though words fail us when we try to describe the meaning and nature of what we experience. It is the same for the ways we undergo the cycle of death and resurrection in our lives. It is not a dogma but an experience. We know we have experienced resurrection in our lives: when something seems to have died in us and yet, even after what might seem a long three days, life is wondrously renewed and expanded. St Augustine said the Resurrection of Christ is more than a belief. It is the essence of Christian faith. It is our faith. And faith – meditation teaches us each day – is pure experience.

So, how do we feel the Resurrection experience?

For sure, not as we feel most other kinds of experience. It is commonly said that millennials prefer experiences to possessions. They are less interested than their parents in buying material things or settling down in stable commitments. They like to go to many places, participate in different kinds of events, do new things and keep their options open. However generally true this is, it is a feature of modern culture. Products are not marketed on the basis of their content or usefulness as much as on the kind of ‘experience’ they are associated with. Serial experiences like this suit the new gods of our time better than the old gods who expected regularity, observance and fidelity.

“Self-knowledge is the light of our spirit illuminating all dimensions of reality”

The gospel tells us that the Resurrection of Jesus is encountered in the spiritual dimension. Experience in the spiritual dimension is faith. It is not part of a series of ever new and exciting experiences – but about the deepening of relationship. This kind of experience cannot be bought or traded or even observed and evaluated from outside. It is as much within as without. Through self-knowledge- the kind in which we know ourselves known, – Christ is formed in us. It is not a one-off. It grows. And so, there are temporary and partial ways of experiencing the Risen Christ. If we try to pin him down, he slips away as he did at Emmaus and, definitively, at the Ascension. And yet, after these partial enlightenments, we do not doubt our experience. On the contrary, our faith deepens.

Why should it be like this? We could think that God is playing games with us or ‘testing’ us. That might be a childlike way of putting it but not so attractive to people today. To understand it, we need to relate to the dimensions of reality we cannot see as clearly as those of time and space. The physicist David Bohm tried to explain how these different dimensions relate by comparing the ‘implicate order’ and the ‘explicate order’. The Implicate order is the deeper reality which enfolds all other dimensions. In this order, space and time no longer dominate relationships between things – or people. It is the ground from which reality emerges. The Explicate order is the unfolding of this, in the way a digital signal unfolds itself to produce images on a screen.

I once met Bohm while waiting for a yoga class, but I hadn’t read him then and we didn’t have time anyway and it wasn’t the right space. Although he was very interested in meditation, he wasn’t religious as far as I know. Maybe his ideas don’t help everyone, but they suggest to me a mystical and scientific vision of reality that resonates with the wisdom of the spiritual traditions. Concerning the Resurrection, it helps us see how the ordinary experience of daily life connects to the experience of that deeper, enfolded dimension in which the Resurrection is fully encountered. There were ‘appearances’, unfoldings, of the Risen Jesus. Ten are described in the New Testament in a way that is both ordinary and mysterious. These encounters transformed the lives of those touched by them. It seemed to them even more real than the physical kind of encounter bound in time and space. Ever since then, down the centuries, lives have been touched by the Resurrection and take a new direction. Without leaving the ground of daily life, they expand into new dimensions of reality. If this were not so, why would we be celebrating Easter this year?

The Resurrection doesn’t make Jesus a god, new or old. His followers are members of a religion bearing his name, but only secondarily. Primarily, they are those whose faith in him and union with him is growing continuously. This unfolds – with ups and downs, as in all relationships – and leads us into dimensions of his reality that astonish the mind and break open the heart. As this is what the Resurrection means, the present time of transition is not the end of Christianity, as so often predicted, but another end in the many forms of the ‘explicate’ Christian order through which it has always evolved and will continue to, until the ‘end of time’.

In the desert, at the foot of Mount Sinai, the chosen people panicked and rebelled and chose other gods. They made the golden calf from their trinkets and worshipped it. When Moses returned and saw the shenanigans going on, he smashed the tablets of the Law (it didn’t seem the right time to deliver them). He then smashed the god-statue, ground it into powder and made the people drink it. They re-owned their projections and tasted reality again.

‘gods’ are projections, splinters of ourselves. That is why they depend on us. We blame them when bad things happen but only dig a deeper hole of unreality and of alienation from our true selves. When we imagine God as a god we do the same. We blame ‘Him’ for ‘allowing’ bad things or for ‘inflicting’ them on us as punishment. The desert and the Resurrection expose the fatal selfdeception in this kind of religious mentality. Meditation, in Christian faith unites the experience of both the desert and the Resurrection, of Lent and Easter. It opens a new kind of religious consciousness for a humanity come of age.

In silence and stillness, we experience that God is present in our suffering, whatever causes it – whether genes or a deranged gunman. Our compassion for those suffering – as we saw globally after the Christchurch tragedy – is itself a manifestation of the spirit of God. If we are the victim, we are empowered to endure in faith what cannot be changed. And we experience the grace that transforms despair into hope, bitterness into love.

Resurrection doesn’t make us immortal. We still die. But it changes the way we live and therefore how we approach death. This is faith. As faith deepens, meaning emerges. We recognise the pattern of the Resurrection experienced over and over from childhood to the end. As I finish this letter, I recognise this pattern once again.

Today in London, as the trees are washed in spring green, we are packing up Mediatio House and the community is moving to Bonnevaux. A leaving and an arriving, a death and resurrection. There is still much to do to complete Bonnevaux; but it’s ready enough for us to start to live there and to celebrate the beautiful mystery of our faith. Please keep all that Bonnevaux can be for the world and for our community in your heart this Easter, as we will keep you in ours.

With much love