Dearest Friends,

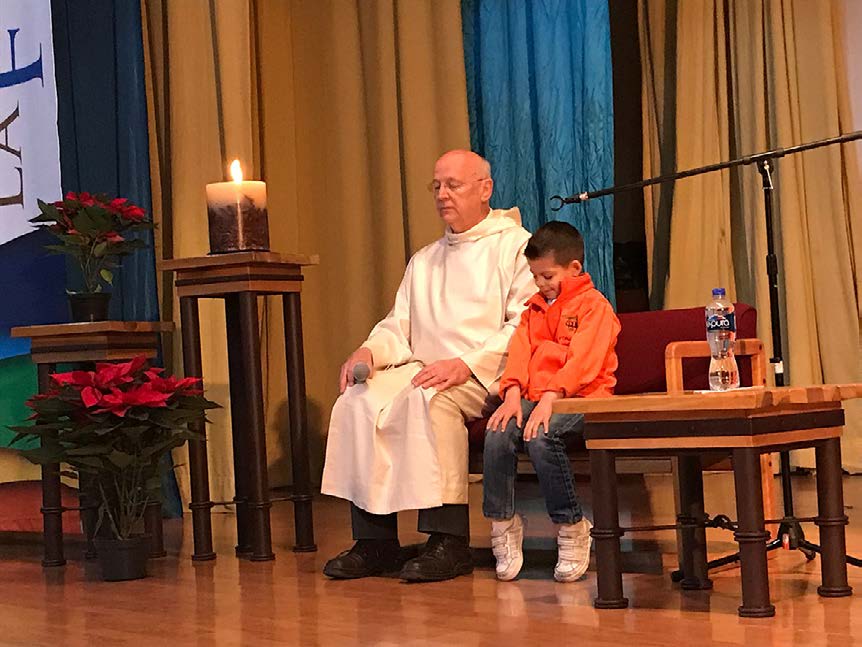

I have just returned home from a trip to Mexico. My first morning there gave me the challenge and delight of meditating with a thousand children in a large school auditorium. I spoke to them in two groups, younger and older, but the quality of the silence we shared was the same for both sessions. They have been blessed with a school and teachers who understand the value of meditation for the young and who have not only added it to their daily schedule but allowed it to pervade the life of the school. The fruits are very evident. On my last morning in Mexico City I met and meditated with a group of business leaders at a breakfast session in an elegant club. I think they were more surprised than the children at the idea of meditating together but they responded well: there is nothing like the experience itself to make one see how normal and sane meditation is.

I told the children that they are the leaders of the future and will soon be inheriting the grievous mistakes of their parents’ generation. The consciousness and balance they are already finding in the contemplative experience will be essential to their way of dealing with the global and personal problems of their lives. I told the business leaders what I have come strongly to believe, that no greater responsibility sits on their stressful shoulders than that of leaders recovering their childlikeness in the experience of contemplation.

The prototype Christian monk Anthony of the Desert speaks to both young and old today across seventeen centuries of human evolution. ‘The time is coming’, he said, ‘when people will go mad and when they see someone who is not mad they will attack him saying ‘you are mad, you are not like us’’. Anthony spoke these words not far from the mosque in Sinai where 305 worshippers were massacred recently by Islamist militants. The victims were Sufis, the contemplatives of Islam, the most peaceful and gentle in their teaching and lives. Anthony’s words and the madness of our times remind us how urgent is the need to recover the contemplative perspective that we have somewhere lost on our global march of progress.

But such has it always been. The Nativity story evokes not only the joy of the birth of the Jesus who is still changing human existence but also the madness into which he was born and in which we still live. The massacre of the innocents by the tyrant Herod and the witness of the first martyr, Stephen, are both remembered close to Christmas. They stop us from seeing Christmas in the sentimental light which modern consumerism confects around us at this time of the year. A newborn child fills the world with happiness even if the world has gone mad. It also evokes the protective concern of parents and family for the health of the child. When we are most vulnerable we are most in need of understanding what health really means.

‘Sanity’ comes from the Latin ‘sanus’ meaning healthy. In good health we feel whole, balanced, sound in body and mind – even if we are suffering or dying. Sanity means accepting and making sense of the whole spectrum of life, the painful as well as the pleasurable. This total acceptance and clarity allows us to live and to die healed.

John Main said that sanity and balance mean ‘knowing the context in which we live’. That is why we are obliged to know what is going on around us. Like many perhaps, I have been tempted recently to opt out, to stop listening to the news, the failures of self-seeking politicians, the shadow side of humanity spilling its raging darkness over the innocent, the greed and corruption of corporations, the Mexican cartels who give schools and social services to poor villages and towns and ruthlessly kill those and their families who resist them. But, to be sane we have to recognise and confront both our own insanity and that of the world.

Understanding contemplation helps us to see this in more immediate, experiential terms. If we are to be attentive to reality, we need to see, to be aware of our inattention and all the disorder it creates around us and between us. This helps to bring the idea of God down to earth. To ‘seek God’, as St Benedict says, means more than thinking or imaging God. It means, more purely and simply, to pay attention. The life of attention is a godly life. It reverses disorder and restores order and harmony to ourselves and to the relationships that compose ourselves. To be devoid of attention, unaware of our selfish mindlessness, is a state of sin from which we are redeemed by the experience of love, which hits us when we are awakened by a source of attention directed towards us in all our unworthiness and insanity.

Awakening to a more attentive and conscious life is an initiation into selfknowledge and so into the knowledge of God. Self-knowledge, the contemplative tradition teaches us, is more than self-esteem or just feeling good about ourselves. It is feeling good because we can see ourselves as we truly are. Humility like this is a great resource for getting through madness. Mere self-esteem often hides dependency on others. When they reject or despise me, I withdraw, react, twitter my feelings to the world and violently reject the rejection I feel. Contemplative wisdom exposes the insanity of this response. Even more (this makes it seem insane to many), it recognises the advantages of suffering rejection. The ego is purified and reduced and the space it excavates in us allows the spirit to expand. No one likes the Cross yet we have to learn to embrace it.

It feels like an entry into a nothingness which is easily mistaken for death simply because we misunderstand the nature of death, failing to see it as the combining of loss and transformation. Enlightened ones, even as different as Francis of Assisi and Simone Weil, understand the advantages of the Cross. An MBA student learning meditation, who told me he did not ‘have a religious bone in my body’, asked if he could write his first essay on the Dark Night. I wondered why and where an irreligious person would even find out about this term, let alone be interested in understanding it. Meditation had taught him quickly by direct experience. His conclusion, comparing mindfulness and meditation, was that mindfulness would be unlikely to lead you into the dark night but that meditation surely would.

In the science fiction film of the future, Interstellar, there is a dramatic scene where the astronauts plunge their craft into a black hole. The very name we give this phenomenon indicates our ignorance about it and the fear that ignorance produces. In the film, however, the black hole, while admittedly a bit terrifying, leads into new dimensions of reality. The human concerns and emotions, love and gravity, survive the transition but the ways in which we see reality and undergo all experience are utterly transformed.

This same transformation happens through the far less terrifying practice of meditation. There we discover that the radical poverty of spirit we enter through the loss of ‘all the riches of thought and imagination’, as the desert monks called it, enables us to awaken to the new dimension that Jesus called simply the ‘kingdom’. The kingdom, like the human self, is unobservable. It is found in a dimension of reality beyond the confines of ordinary self-consciousness and our persistent illusion of ‘objectivity’. Although this may sound abstract and over-subtle it is without doubt children who experience and can even understand it more easily than we with our business-oriented minds.

The self is always invisible – that which ‘no one has seen or can see’. Our personality by contrast is most of the time only too visible. We look at it in the mirror of the mind all the time. But we cannot see consciousness. Consciousness is seeing. In the dimension of reality we call contemplation we know what is beyond knowledge through a work of unknowing, the laying aside of the conceptual and image-making mind. We learn that we can know without always being stuck as an observer. More than self-awareness, which is necessary for accomplishing mechanical tasks efficiently, self-knowledge is born amid the labours of consciousness and awakens us to the fact of our being on a journey. This journey spans dimensions of reality and the stages of human development. Yet, however different these dimensions and stages, the journey is one and its irreducible oneness is the meaning of the self.

Attention requires what our world has sacrificed to the acquisition of speed: stillness. It is possible to be moving fast and remain still, in a state of attention; St Benedict tells us to ‘run along the way of the Lord’s commands’ and that ‘idleness is the enemy of the soul.’ The contemplative life is not about inertia. Of course the speed at which one runs and remains busy will vary with individual temperaments and even the most resilient and energetic need times of slowing down to a still point – just as we all need some space for emotional solitude. But modern life, hijacked by our technology at the ransom of our spirituality, has lost the art of the balanced life and the wisdom to know what this means.

Surprisingly for the fast-moving types, stillness is energising for body and mind. Early in this journey, almost from the beginning (though there can be a honeymoon phase), it becomes clear that we are not just into relaxation or stresscontrol. We need to deal with the innerconflicts and contradictions that the distracted life keeps undercover. Soon we see that there is no one to blame except ourselves. Even those who have suffered injustice are denied the luxury of remaining a victim. This may sound harsh but it is what all therapy is designed to show, including the powerful therapeutic influence of a daily contemplative practice.

Similarly, we must forego a prolonged state of discouragement (acedia) as this would lead eventually far away from the revitalising experience of stillness and straight into the sidings of stagnation. Loneliness, too, one of our age’s most corrosive illnesses of the soul, needs to be faced and re-evaluated. Meditation turns it back into the solitude out of which every conscious and living relationship is generated. Loneliness is the failure of solitude.

These and many other elements of the work of contemplation show us that the work is a constant intertwining of repentance and growth. Metanoia is the narrow path into the kingdom, a turning around of our attention and so of all mental states. This pivoting is continuous. It demands tough self-awareness of our faults and failures but frees us from lingering guilt or self-rejection. Out of self-criticism comes a truer sense of our potential and essential value. We come to see our real potential in the light of our accepted failures rather than in the light of fantasy.

Without a strong capacity for attention the centre is lost and things begin to fall apart. More and more energy is then needed to hold the disintegrating elements together. Life begins to feel, as it does to many today, like an endless struggle with no worthwhile meaning. Attention, however, quickly changes all this. It awakens the undiluted and undistracted experience of being. To the distracted person this experience feels at first like nothing leading nowhere. In asense it is. But it will take time to appreciate the meaning of the experience: and then one sees that no where is now here.

So, we can become sane again and helps others to do so. Even with the world continuing in madness sane people can make a difference, especially if they remember what it was like to be insane. In Christian wisdom, contemplation is felt to be gift or grace, not the result of will power, scholarship, imagination or spiritual technology. Yet, because contemplation involves an ever fuller participation in reality, not an observer’s distance, it does ask for ‘right effort’. We need to do something in order to learn what it is to be. Then being shows itself as pure action and we return to the mundane world of work with new motivation and insight.

We meditate in order to be contemplative, which is an end in itself. Nearly everything in our world has become an instrument, a tool for achieving something else whether it is fame, money or self-gratification. All streams of human wisdom agree that contemplation is an end in itself and justifies itself. What flows from it – compassion and wisdom – need to emerge from this non-instrumentalist attitude. Contemplation then turns the toxins of madness into medicine. It is always open-minded and openhearted and turns away from ideological or sectarian options. In this, religion and science agree in the value of the contemplative mind.

“Even with the world continuing in madness sane people can make a difference”

‘Contemplation’ contains the word ‘templum’. But templum originally referred to the space in which a ritual was performed or a structure (like a temple) might be built, not the physical building itself. The meditating mind is boundlessly spacious and yet always capable of acuity and focus. Structures rise and fall, just as thoughts and certainties come and go. Spaciousness is the Spirit and, when we are in it, we are detached from whatever physical or conceptual structures may occupy the space for the time being. There is always an inbuilt tension between a structure and the space which it occupies. So, there is a timeless tension between contemplation and religion. When it is in balance, this tension protects sanity. Its collapse presages madness.

The capacity for contemplation is innately human. Even those who convince themslves ‘I can’t meditate’ have the gift of this capacity both to enjoy the present and to transcend. Children and atheists testify to the universality and unconditionality of the gift of contemplation. It is, Jesus knew, a truth often hidden from the learned and the clever and revealed to mere children. It is never the possession of the religious. In a world gone mad such a resource has immeasurable significance. The contemplative person channels anger into healing and re-constructive action. It purifies and reforms religion and so helps us see what new role religion is meant to play in the future. It corrects and heals; it does not, like many remedies on offer today, make us madder.

To appreciate the gift of contemplative practice (like meditation) in one’s own life will eventually make one aware of its social value as well. Its capacity to change the world is proven by its ability to transform us personally. A nine-year old meditator, a little girl told me recently, when I asked her when she meditated at home. ‘whenever I have a big fight with my sister’. To recognise that anger is unpleasant for the angry person to feel but that it can also be internally cured is wisdom. Wisdom for a violent world. The symptoms of contemplative consciousness affecting the body politic and the financial structures of society can be expressed in the classic formula of the secularised French Revolution: liberty, fraternity and equality. Without a transformed mind these ideals quickly deconstruct and there is no quicker passage to violence than to have one’s ideals exposed as illusions.

A mind liberated from its own structures and its illusions gazes on other people with fraternal and sisterly love. To those we love we attribute value and importance equal to our own. Families and communities are the laboratory and the lampstand of this experience of the kingdom. And although they may generate many failures and have all the faults of the ordinary, these seminal social groups are needed by society to testify to a necessary redemptive hope even in the grim face of collective madness.

As an idealistic young man I was drawn to the vision of community created by meditation as a ‘community of love’. I have failed it many times and in many ways but I have never lost the vision or the conviction that it is achievable. From being a vision held by me and a very few, it has grown, through the community, as one that is now embedded in many singular lives, meditation groups, friendships and national communities. Such a vision lives or dies in the individual but it is realised in the body of the community.

At the blessing of Bonnevaux a few weeks ago I felt that we are already embarked on a new phase of this long journey. It is a young, fresh and fragile phase. Like anything young and growing it needs much nutrition and care in order for it to mature well. Whenever Bonnevaux becomes the centre of peace and for peace that we pray it will, a place of creative thinking as well as deep contemplative practice, I think all the sacrifices we have made for it will be justified. Bonnevaux cannot save the world. But it is a partial manifestation of something, a movement of consciousness, a wave of contemplation, that is sweeping the world and that we can confidently affirm can pull us out of madness into a new sanity and a new kind of sanctity.

On any long journey like this, a companion is a blessing, at times a necessity. What is considered the first work of literature, the Gilgamesh epic, composed more than four thousand years ago in a Sumerian culture, the goal of the human quest is interwoven with the experience of friendship. Gilgamesh is a strong young warrior who becomes proud and tyrannical. His subjects pray for relief and it is sent in the form of Enkidu, a somewhat wild man who becomes the intimate friend of Gilgamesh after he has been civilised and fought Gilgamesh. They go off together on a great quest in the course of which Enkidu is killed. Gilgamesh is grief-stricken and inconsolable but also tortured by a sense of his own mortality. He continues the quest alone and returns to his city a better man and a far better leader.

This epic awakens and portrays the major themes of human consciousness. It shows us, for example, that we cannot mature alone and that we must suffer the loss of what we love in order to achieve transcendence and wholeness. One might see in both these ancient friends, Gilgamesh and Enkidu, archetypal elements of the Christ-mystery to which the end and beginning of each year, this sad-happy tipping-point of time, invites to pay deep attention. ‘God became human in order that the human being might become God’. This shocking revelation, repeated by the earliest teachers of the Church, from the Alexandrians to the Cappadocians, plunges us into the twinned mystery of the incarnation and divinisation revealed by the birth of Jesus of Nazareth. In him we see both ourselves and the friend who is always another one’s self.

The humble, imperfect work of contemplation – as ordinary as daily meditation – awakens and transforms our sense of self. It sheds an illuminating light on the scriptures of our own tradition as well as on the wisdom texts of others. It renews the language which we need to express and share our human journey of faith. Loving God then means more than agonising about God’s will and ‘doing what He want’s. It evokes the human attraction to love that is powered by the capacity to turn from self-consciousness and focus our attention on another. When this awakening is happening we know that we are not asleep and that we cannot deny, reject – or for long forget – the essential fact of being which is the true arbiter of the good. To love is simply to be awake in all we are and do.

Birth is the continuous present of reality. Christ, as the mystics down the ages have taught, is continuously re-born in us. He forms himself in the womb of consciousness through the work of recognition and acceptance. To know that we are recognised and known awakens our ability to recognise and know. The more we grow in attention, the more humble becomes our desire to be conscious. Christ’s self-formation in us is our transformation and our progressive divinisation. As we become truly ourselves we can understand why the Christian says ‘I live no longer but Christ lives in me’. The I that no longer lives is the old self, Gilgamesh before Enkidu. The I that can say this knows that it is never alone but now lives continuously in the deepening solitude of its uniqueness.

With much love,