All of John Main’s theology and teaching on meditation is not only based on experience but also on Scripture. Every teaching of his starts and/or finishes with a quote from Scripture. This same emphasis on Scripture is also found amongst the early Christians and the Desert Fathers and Mothers. They were all on the whole still part of an oral culture; the Desert hermits listened to Scripture at their weekly gathering, called ‘synaxis’, rather than read it personally. This is clear from St Antony’s saying: ‘You have heard Scripture. That should teach you how.’ The words of Scripture were held to be sacred and demanded full devoted attention. We hear a young monk being told off by Abba Nau, an elder, in these words: “Where were your thoughts, when we were saying the ‘synaxis’, that the word of the psalm escaped you? Don’t you know that you are standing in the presence of God and speaking to God?” After this they would return to their cell and ruminate on what they had heard and in doing so they would commit it to memory.

St Antony (251-356) was the example the Desert Fathers and Mothers held before their eyes, although he was not the first hermit in the desert – he himself visited several solitaries in the beginning of his journey. Athanasius, an influential early Bishop, wrote ‘The Life of Antony’ in Coptic (357), which encouraged Coptic Christians to move to the desert with Antony’s words and Scripture as their guide as to how to live their life. They kept in their mind and heart his advice: “Wherever you go, always have God before your eyes; whatever you do have before you the testimony of Scripture.” The same emphasis on Scripture we find in the Celtic tradition – John Main’s heritage: “Through the letters of Scripture and the species of creation the eternal light is revealed.”(John Scotus Eriugena 9th c)

Origen outlines systematically in his most important work ‘On First Principles’ a slow, profound and attentive way of reading Scripture. He emphasizes that there are four levels of reading Scripture. He starts by pointing us to the first level of reading Scripture: taking the text literally, concentrating on the surface meaning – and that is important in itself. But he emphasizes that we need to go beyond that to the moral teaching implied. Following that, he encourages us go even further and look at the allegorical meaning of this passage. In this he was in perfect accord with St Paul: “Our sufficiency is of God who has also made us able ministers of the new testament; not of the letter but of the spirit; the letter kills but the spirit gives life”(Paul 2 Cor 3:6) This in turn would finally lead us to be confronted with the spirit of the given text, an encounter with the risen Christ, the essence of Scripture for Origen: “This is how you are to understand the Scriptures – as the one perfect body of the Word.”

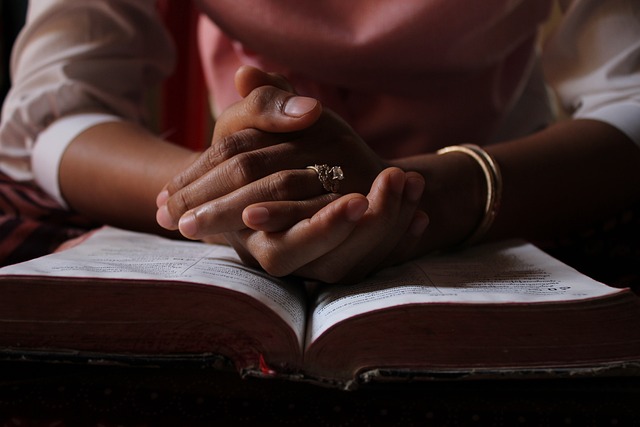

There is an excellent foundation for this discipline in Scripture. In Luke we hear: ‘Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart.’ (Luke 2:19) When we follow Mary’s example we read with the ‘eye of the heart’, intuitively. We engage deeply with the text in a gently attentive and reflective way. This way of engaging with Scripture came to be known since Origen as the discipline of ‘Lectio Divina’. This became from the 6th century onwards an integral part of the Benedictine way of prayer, which John Main as a Benedictine monk heartily endorsed.