When John Main became a monk, he “was given another method of meditation which [he] accepted in obedience in [his] new status as a Benedictine novice.” He explains in The Gethsemane talks: “In retrospect I regard this period in my life as one of great grace. Unwittingly my novice master had set out to teach me detachment at the very centre of my life. I learned to become detached from the practice that was most sacred to me and on which I was seeking to build my life. Instead I learned to build my life on God himself.” His faith that “God would not leave me forever wandering in the wilderness and would call me back on the path” was justified. I will leave you to discover in the book itself how John Main was led to Augustine Baker’s book Holy Wisdom and in turn to Cassian’s Conferences. In John Main’s words: “It was with very wonderful astonishment that I read, in his Tenth Conference, of the practice of using a single short phrase to achieve the stillness necessary for prayer – ‘The mind thus casts out and represses the rich and ample matter of all thoughts and restricts itself to the poverty of a single verse’. In reading these words in Cassian and Chapter X of the same Conference on the method of continual prayer, I had arrived home once more and returned to the practice of the mantra.”

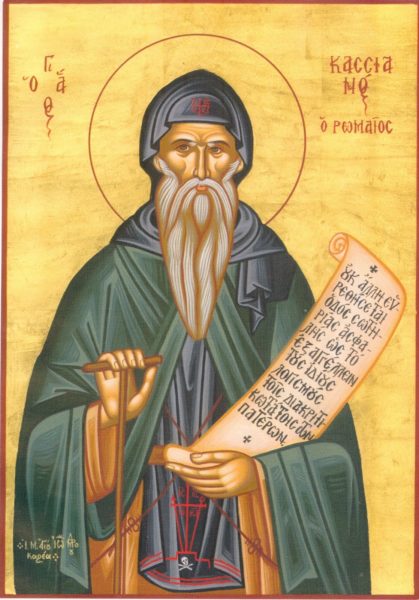

John Cassian (365-435) was strongly influenced by Evagrius, whom he revered most amongst the Desert Fathers and Mothers. But we see from his Conferences that he sat not only at the feet of Evagrius but also at the feet of at least 15 other Abbas and Ammas, and made their teaching his own as well. He softened some of the harshness of the desert teaching, simplified it and adapted it to the environment of Southern Gaul, where he established two monasteries – one for men and one for women – when he left the Egyptian desert. Moreover, he created unity out of diversity: he formulated a coherent system of practice and thought based on the individual sayings and teachings of the Desert Abbas and Ammas. He is really the one responsible for bringing the desert tradition to the Latin West and in doing so exerted a great influence on St Benedict and the whole western monastic movement. Despite the fact that St Benedict recommended his monks to read Cassian every day, this practice has been neglected over the centuries in the Benedictine tradition. John Main and Laurence Freeman have brought it again to the attention of the Christian world and their Benedictine brothers and sisters. Again John Main did not take Cassian’s teaching just as he found it but he too adapted it – this time not just for monastics but for lay women and men of the 20th century.

Cassian’s teaching based on that of monks from the Egyptian desert of the 4th century CE and the teaching of a Hindu Swami in the 20th century proves how universal this way of prayer is. We find the same insistence in both on using a phrase as an aid to bringing our busy minds filled with thoughts to stillness. Both Cassian and Swami Satyananda see this repetition of a prayer phrase as an important preparatory stage, a way of detachment, a way of training the mind to achieve single minded effortless attention, leading to the prayer of stillness, contemplative prayer with the ultimate objective of becoming aware of God’s loving presence in our hearts.