The familiarity of many of the parables and two thousand years of commentary on them could mean we no longer read them with fresh eyes or hear them with fresh ears. Sometimes we think, ‘I know what this one means.’ Amy-Jill Levine’s book invites us to look in new and unexpected ways and to be open to an alternative perspective. It is a book especially helpful for those practicing Lectio Divina on the Gospels.

There are said to be 40 parables in the Gospels (Jesus in John’s Gospel uses imagery rather than parables). They occupy fully 35 percent of the first three Gospels, suggesting that the short story was the major and preferred teaching method of Jesus. But one of their most surprising features is that they are not about God. They are about weddings and banquets, family tensions, muggings, farmers sowing and reaping, and shrewd business dealings. God is mentioned in only one or two. Jesus, it seems, wants us to look closely at this world in all its contradictions to see how the Divine is still present. Amy-Jill Levine gives us the invitation to revisit this great story-teller by looking first at the details, the characters, the contexts and plot before we leap into the message the parables contain.

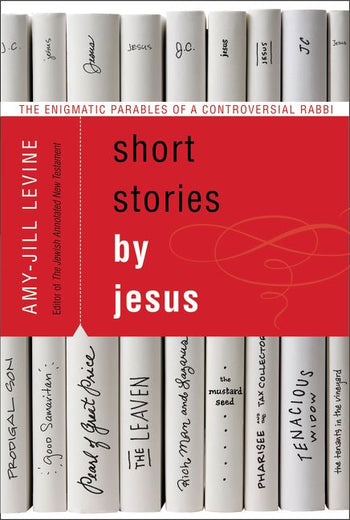

Amy-Jill Levine is a scholar from the Jewish tradition who has dedicated herself to the study of the Christian Scriptures. She is the editor of the Jewish Annotated New Testament. In this (her third book published by Harper-Collins) she seeks to jump past two thousand years of Christian interpretation to the historical context of the time of Jesus. Her study is an attempt to uncover what would have been the responses of Jesus’s original audience. She asks whether, with a leap of historical imagination, we can bracket later Christian interpretation and ask ourselves how his parables might at first have been heard.

She makes a number of important introductory points:

One, that Jesus was not speaking to Christian communities but to practicing Jews. The Gospels, on the other hand, were written some seventy to ninety years primarily for the Christian community. Some of the perspectives of the Gospels may thus have been shaped by conflicts of the early Church with Judaism, such that Jewish religious leaders became obvious ‘bad guys.’ Jesus’s critique of religious personages in the parables became, within a generation, a critique of Judaism itself.

Two, there was a taste in the early common era for allegorical reading. The original audience of Jesus’s stories would have heard the parables primarily as stories. They would have been more interested initially in the characters depicted in them than in the meaning or lesson derived from them. The danger of allegory is that we miss the details because we think we already know what the meaning is. Maybe it is the aspect of self-knowledge which is lost when we leap too quickly to the allegorical meaning of Jesus’s parables.

Three, by considering the literal meaning of Jesus’s parables we get the shock value, and even subversive humour, of this master of the parable. Amy-Jill Levine calls this, “the power of disturbing stories.” If the parables do not perplex us we may have domesticated what was once a very provocative tale. After two-thousand years of interpretation we have become a little too habituated to what would have seemed quite paradoxical and unexpected to Jesus’s audience. It is in the anomalies of Jesus’s parables that we may get hints at more rounded – maybe more human – interpretations.

Four, Jesus’s parables go out of the way to mention the good and the bad alike are both under God’s compassionate gaze. We are all, in fact, a mixture of both. Wheat and tares grow together in us and Jesus’s parables are wonderful at showing the mix in each character. But often we read them with a polarised ‘good guy, bad guy’ outlook (often backed up by anti-Jewish sentiments in Christian exegesis).

Some examples:

In the parable of ‘the lost sheep’ the shepherd goes after the stray to his own detriment – leaving all the rest of his sheep to stray and the extreme discomfort of carrying one home. The story subverts the world’s standards of what is good shepherding.

In a number of parables the idea that Tax Collector is ‘good guy’ and Pharisee is ‘bad guy’ is the opposite of the way Jesus’s original audience would have seen things. Tax Collectors didn’t just take your money but they were collaborators with the Romans and notoriously corrupt. Pharisees were a reform movement that tried to make Jewish practice relevant to people’s lives at a local level, in synagogue not just the Temple, and were generally respected for their effort to do so. Jesus may have been giving the Pharisees a hard time because (in the same way as he challenges the expectations of what good shepherding was) he is trying to challenge the standards of what good religion is.

In the story of the Good Samaritan the Priest and the Levite walk past on the other side of the wounded man. Christian interpretations soon argued their lack of compassion was due to Jewish religious laws – contact with what was potentially a dead body rendered anyone about to officiate in the Temple ritually ‘unclean’. Such a reading, however, ignores the fact that in the story all the travellers were going “down the road from Jerusalem to Jericho.” Priest and Levite were not going to be serving in the Temple the next day. At all other times the Jewish law was to help the wounded or bury the dead. So, it was not the Jewish religion that kept them from compassion but rather their own cowardice – robbers may still in the vicinity…

In the parable of the yeast-leaven mixed in with three measures of flour (Matt 13:33) Christian commentators argued that this parable prophesied the inclusion of the ‘unclean’ gentiles into the Church because unleavened bread was proscribed for the Jewish Passover. But for Jesus’s audience the fact that 364 days of the year it was perfectly normal for Jews to mix leaven with their flour meant that the action of the woman in the parable would have been no shock. The surprising thing is not the yeast but the three measures of flour which amounted to about fifty pounds weight – enough for some 700 biscuits! The dough would have been far too much for one woman to knead on her own, and the yield would be far too high for one person to consume. The image is one of extravagance, or hyperbole. Jesus’s original audience would have understood this, but later interpreters focussed on what would not have been an issue for Jewish hearers, except for one day in a year.

In the parable of the sower the remarkable thing is not the nature of the ground – the countryside in Galilee and Judea is a mix of paths, thorns, rocks and open ground – but the extravagance of the sower who does not seem to be fazed by such concerns, who flings seed everywhere. It is this Jesus’s original audience would have noticed as somewhat foolish but as expressive of the generous abundance of God’s love.

In the parable of ‘the Pharisee and tax collector praying in the temple’ (Lk 18:9-14) the excess of one’s man’s practice repairs the deficit in the other, as one man’s humility brings down the pride of the first. The Pharisee (in fasting twice a week and giving a tenth of everything he possesses) is doing much more than is expected in Jewish practice, as the tax-collector (because of his profession) is doing less. But the Pharisee is pleased with himself and the tax-collector penitent. According to today’s translators, Jesus ends the parable saying that the tax-collector “went down to his home justified rather than the other.” But the Greek word Luke uses (here translated as rather than) is ‘para’ which can just as well mean ‘alongside’ (as in ‘parallel’ or para-Olympics’). It also has the meaning of ‘on the side of’ or ‘on behalf of’ (as in ‘paraclete’ – lawyer for the defence, or ‘parable’ – story that serves a message). The parable is then, as Luke says, directed against those who “believed in themselves they were righteous” (Lk 18:9) in-so-far as righteousness, in Jewish understanding, comes from being part of a community.

In ‘the prodigal son’ story, we assume the father symbolises God but the Jewish audience of Jesus’s time may have felt that, in relation to his sons, this father was not very prudent. It was not usual to give a son his inheritance simply on request. Indeed, the expectation of a father – as expressed in the book of Proverbs – was to protect a growing son from his own dissolute tendencies rather than to indulge them. Likewise when this son returns home, the older brother is not told but only finds out from a servant when the party is in full-swing. Poor communication can lead to one member of a family feeling left out. Humanly this is a parable of a dys-functional family: over-fond father, self-serving and jealous sons, and an absent mother.

In ‘the treasure hidden in the field’ (Matt 13:44), a man finds a treasure, well and good, and the treasure may symbolise God or Christ, but the interesting detail is that in order to own that treasure the man has to buy the field, otherwise he is merely a thief (though nobody else may know). Finding the treasure is not enough, the treasure must be appropriated honestly. This treasure is not ‘cheap grace’ but the costly grace that asks from us all we have, just as the man in the parable ‘in his joy went and sold all he had to buy the field.’ Likewise, ‘the pearl of great price’ (Matt 13:45-6 is not just a lucky find, but a demand that costs not less than everything. In fact, unless the man sells the pearl again he has nothing to live on. Maybe any pearl we get must be passed on.

There are many parables where the evangelist gives a clue as to what the purpose of the story may be, e.g. ‘the widow and the judge’s story was told, Luke says, to impress ‘the necessity always to pray and not to become discouraged’ (Lk 18:1). There are some parables where Jesus’s own interpretation is recorded by the evangelist, where he says ‘listen then to what the parable of the sower means…’ (Matt 13:18) , or where his disciples ask, ‘Explain to us the parable of the weeds in the field’ (Matt 13:36) and he does. Amy-Jill Levine rather disconnects these interpretations – whether in Jesus’s own voice or in that of the evangelist – from the parable itself. I wonder if she is a little unfair in splitting the early interpretations of the parables given in the Gospels from the way Jesus’s original audience would have reacted. Amy-Jill Levine is quite good at showing what the parables are quite likely not to mean (and helps clear up some later Christian interpretations) but she is not so strong in showing what they do mean. It is notoriously hard to to say, in the transmission of an oral into a written text, what is the ‘original’ intention. Stories become our responses to them. Jesus’s disciples were part of the audience that first heard him, the written Gospels come from their witness. No doubt they sometimes misunderstand what he said, but as readers of the parables we are dependent totally on their witness.

At times Jesus may be expressing his own deep understanding of Jewish wisdom, at others he may be subverting or even changing the way Judaism had ever been interpreted before. Amy-Jill Levine never comments on the very fierce critique Jesus gives (or is reported to give) of the Scribes and Pharisees. It is hard to see this as a critique of particular inauthentic religious or simply the result of a later Christian grievance with Judaism. Jesus does seem to be laying the axe to the root, not of Judaism, but of the self-serving and hypocritical tendency of all religion.

Amy-Jill Levine helps show that interpretations of Jesus’s parables both in the Gospels themselves and in later Christian exegesis may be coloured by the internecine strife within the Judeo-Christian tradition. Her book invites us to a fresh look at origins: interpretations of parables are not ‘explanations.’ Where such keys are given they may unlock some aspects but should not be accepted uncritically and are not exhaustive. To be told that a parables was told for “that purpose” or “means this” should in no way stop us from exploring what it means for us and from our own experience. Most of the parables in the Gospels anyway do not come with the evangelist’s comment, where there is a key given it may elucidate the story but we are also meant to grapple with them for ourselves. Amy-Jill Levine’s book is a helpful prompt to a more personal Lectio Divina, a safeguard against stereotyped anti-Semitic readings but most of all, by seeing a different side to the story we come to see there are many sides to any great story.

Images sources: book cover by harpercollins.com

7 thoughts on “Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi, by Amy-Jill Levine”

I read this careful and extended review of Amy -Jill Levine’s book with great interest, and I am especially grateful for the many parables and their possible interpretations given in the review.

…..maravilloso resumen de este libro. Gracias.

The Jewish Annotated New Testament, edited by Levine, is a great resource, providing insights from a Jewish perspective that often illuminate the meanings in the text in fresh ways.

An excellent review thank you so much. Now I must get myself a copy and immerse myself in some “new thinking” – I look forward to that! Thank you once again.

Thank you for this full review . I read her book a few years ago and am prompted to do so again. Parables as koans pointing to something beyond the literal, o rculturally prejudiced assumptions.

“…by considering the literal meaning of Jesus’s parables we get the shock value, and even subversive humour, of this master of the parable. Amy-Jill Levine calls this, “the power of disturbing stories.”

I’m going to get the book and have several people to share it with. Thank you Stefan for a clear and well presented summary of the scope of the parables covered. Pat Prescott

This is a very thoughtful and balanced review as well as an encouraging invitation to read Levine’s book; and to engage with – again and for the first time – these ‘enigmatic parables of a controversial rabbi’. The reference to Levine’s work, The Jewish Annotated New Testament, has also piqued my interest and I’d welcome thoughts or feedback on this as well.

Many thanks for this.